I began this post in 2017. The original focus was Louis MacNeice’s’s poem “Brother Fire”. MacNeice was a fire-watcher during the London Blitz which meant that he spent nights on rooftops watching for, and reporting, fires caused by incendiary bombs.

The poem expresses a human kinship with the destructive power of fire:

O delicate walker, babbler, dialectician Fire,

O enemy and image of ourselves,

Did we not on those mornings after the All Clear,

When you were looting shops in elemental joy

And singing as you swarmed up city block and spire,

Echo your thoughts in ours? ‘Destroy! Destroy!’

MacNeice was not alone in his ambivalence. There were others who saw the destruction of the City’s old firetrap office blocks as an urban planning blessing in disguise and the clearance of Victorian warehouses as an opportunity.

MacNeice’s reaction was not as extreme as that of the poet Hugh MacDiarmid who at one point rejoiced in the destruction of London (one wonders how he felt about the bombing of Glasgow). It remains unsettling nonetheless when one thinks about people and not only real estate.

And then, June of that year came the unmitigated horror of the Grenfell Tower fire and its reminder of the enduring callous indifference of authority to the welfare and safety of people. And I put the post aside.

This painting below shows an incident in Shoe Lane in the City of London on the night of 29 December 1940. It’s where today Goldman Sachs has its offices.

There’s a plaque on the wall in memory of Sidney Alfred Holder.

He was a 33-year-old firefighter who, a year before, had been a railway porter. He was crushed there by the red-hot masonry of a collapsing wall. He was one of sixteen firemen killed that night. 500 were injured.

The air raid warning went off around 6pm that night and the fires began at 6.30. Before the night was out over three thousand had been reported to the City of Westminster Fire Control Centre.

Sansom and Rosoman were in a three-man team sent out just before 7pm to deal with a fire spreading on the roofs of Shoe Lane in EC4 – a narrow alley of houses, newspaper offices and a huge Victorian book warehouse.

They arrived at the scene in a commandeered London taxi towing a single fire pump and hoses. When they arrived, the burning five storey book warehouse was already dangerously hot from the inferno inside. By 7.15pm they had deployed their hoses: the pump’s capacity was 500 gallons per minute and they aimed their hose into the blaze.

They were in a narrow alleyway known as Wine Office Court that ran from Dr.Johnson’s house in Gough Square to Shoe Lane off Fleet Street. For the next three and half hours they fought a losing battle to contain the fire.

Rosoman had been holding the hose for several hours when a supervisor asked him to help haul a hose up onto the roof of a nearby building. Sidney Albert Holder took his place beside William Sansom.

No sooner had Rosoman entered the building when he heard the “most godawful noise”. The wall he had left just moments before started to buckle and fall, filling the whole alleyway and burying Holder beneath blazing hot bricks.

They started to tear at the burning debris. When they finally found the dying man his steel fireman’s helmet was, Rosoman recalled, flattened “like a plate”. It was some weeks before Rosoman was fit, mentally, to return to work.

This was the scene that Rosoman depicted in his most famous painting – “Falling Wall”. The other fireman, the author William Sansom, survived. Read his short story “The Wall” below.

The painting was exhibited in the Firemen Artists exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1941. Rosoman said later that he dislike it, considering it too literal a response. To me it remains a powerful snap-shot of a moment of pure terror.

Rosoman had joined the auxiliary fire service – AFS – when WW2 was imminent and he continued to serve until April 1945 when he was appointed as an official war artist with the British Pacific fleet.

This all happened on the night of December 29-30th 1940 – the night of the second Great Fire of London. The bombing of London had begun in September, but this night was a concentrated attack on the square mile of the City. It was the most destructive raid on London of the war with much of the damage caused by fires started by incendiary bombs. More than 100,000 incendiaries and 120 tons of high explosive were dropped on the square mile of the City that night.

The hundreds of fires joined forces The Daily Herald journalist Peter Richie Calder was watching from a rooftop: “Johnson’s London, those narrow back courts which are the hinterland of Fleet Street, was a flaming acre.

The attack was strategically timed for low tide to reduce the availability of water from the Thames to fight the fires.

It was a strike at the heart of the financial district, Fleet Street and the symbol of St. Paul’s Cathedral. It was designed to cripple the economy, destroy key communication networks, erase the symbols of history and cultural identity and bring the country to the point of surrender and despair.

The City – well-known for its historic churches and civic institutions – was also a strategic military target and a Luftwaffe priority. Among the specific targets were the Wood Street Telephone Exchange, the London Telephone Service, and the General Post Office telephone and telegraph services. The six railway stations and the bridges across the Thames were also priority targets.

The plan had three phases:

-

- Phase 1 – Thousands of small incendiary bombs designed to set thousands of fires and light up the City for the next wave. In the first 45 minutes alone, over 10,000 IBs fell on the area surrounding St. Paul’s. There were thousands more to come.

- Phase 2 – A wave of heavy explosives to deepen the damage and overwhelm the Fire services with a firestorm that would suck the oxygen out, creating hurricane force winds to spread the devastation

- Phase 3 – A second wave of high explosives to finish the City off. Luckily for the City, bad weather closed in at the airfields preventing the bombers from taking off to complete this phase. By midnight, heavy rain had shut down every bomber base in northern France. The second strike was cancelled.

“St.Paul’s Must be Saved At All Costs”

Paternoster Square – right by St Paul’s – was for centuries the centre of the book publishing industry. And nearby, there were block upon block of locked four and five storey warehouse and office buildings with no one – on a Sunday – to extinguish the incendiary fires when they started. Many building dated from the middle ages and were tightly packed in narrow alleys and lanes. Others were Victorian.

This network of narrow streets was home to the press, textile, and publishing industries. It was all highly combustible. It was a tinderbox. Between five and six million books went up in flames that night.

By 7 pm that Sunday night three separate fire zones had broken out. The largest, nearly three-quarters of a mile long and a quarter-mile wide, surrounded St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Everything, every street and every building to the north and northeast of St. Paul’s Cathedral, would burn in one vast fire. Walls of fire-weakened buildings would flame up before crashing down into the street with a deafening roar of red-hot brick, debris and smoke. The area from Aldersgate to Cannon Street, all of Cheapside and Moorgate, was in flames.

Before the war began the Dean had re-formed the St.Paul’s Watch group that had helped protect the cathedral during the Zeppelin raids of WW1. They knew it would be a big task and they recruited architects over call-up age – between forty and sixty – who could climb the stairs and navigate the complicated geography of the building. It was a complex task. St. Paul’s was like a ship with six decks is how one watcher described it, with eight main roofs and an array of flat and pocket roof areas.

They installed tanks, baths, pails of water and buckets of sand at vulnerable points about the roof.

I focused at intervals as the great dome loomed up through the smoke.The glare of many fires and sweeping clouds of smoke kept hiding the shape. Then a wind sprang up.Suddenly, the shining cross, dome and towers stood out like a symbol in the inferno.The scene was unbelievable. In that moment or two, I released my shutter.– Herbert Mason, Chief Photographer for the Daily Mail who was on the roof of the Mail’s office at Northcliffe House, Carmelite Street.

While Mason took his iconic photograph he knew nothing of the high drama taking place in St Paul’s.

The whole building was enveloped with the smoke from the blazing buildings nearby. From the street it looked as if the dome was on fire. The bright white sputtering light of the bomb made it look as if the fire had taken hold and the cathedral was about to burn down.

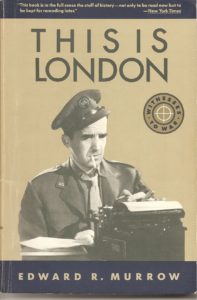

“This is London …. Good Night and Good Luck”

In his live short wave broadcast from London earlier that day Edward R. Murrow of CBS had reviewed the year for his listeners in America – a year of “blasted hopes, futile ambitions, false confidence, small men, and a wreckage of proud and pleasant nations.”

In America, President Roosevelt was also talking on the radio addressing his fellow citizens in a fireside chat, reassuring them that America was not about to enter the war:

The experience of the past two years has proven beyond doubt that no nation can appease the Nazis. No man can tame a tiger into a kitten by stroking it. There can be no appeasement with ruthlessness. There can be no reasoning with an incendiary bomb. We know now that a nation can have peace with the Nazis only at the price of total surrender.

America he said “must be the arsenal of democracy” producing the planes and ships and guns and shells to arm Britain in its fight for survival. Earlier in the month he had explained lend-lease as akin to lending your hose to a neighbor whose house was on fire.

After his broadcast Murrow headed toward the red glow from the east. He met other American journalists on the way and they walked up Ludgate Hill and drew as close to St Paul’s as they could. There are various accounts on-line that Murrow broadcast live from a street near St.Paul’s in which he reports that St.Paul’s was on fire and destined to burn down.

Tonight, the bomber planes of the German Third Reich hit London where it hurts the most—in the heart. And the church that meant most to Londoners is gone. St. Paul’s Cathedral, built by Sir Christopher Wren, her great dome towering over the capital of the Empire, is burning to the ground as I talk to you now.

As Murrow did or did not make that broadcast the St.Paul’s Watch were making their way toward the bomb. It stopped sputtering and the heat from the 4,000 degree melted the lead that held it in place. The bomb dislodged from the roof and slid down the outside of the dome. It landed in the Stone Gallery walkway that circled the dome and was extinguished with a sandbag.

Many Christopher Wren churches were destroyed or damaged that night. But St. Paul’s was safe.

Why did St.Paul’s survive when all around was burned down? Was it divine intervention? Luck and gravity? The concerted efforts of the Fire Watchers to extinguish all fires and incendiaries before fire could take hold? Or was it that the Luftwaffe – or some of the bomber pilots at least – saw the huge dome that gleamed white in the moonlight as a convenient navigation point and therefore spared it?

In 1944 William Sansom’s short story The Wall was published in the literary journal, Horizon

It’s a powerful companion to Rosoman’s painting.