Leonora Kathleen Green (1901–1966)

Novelists and film makers often struggle to find the right period details to anchor their work in a particular era.

And when it’s a much mined time and place – London in WW2 for example – it often results in rolling out the same set of shorthand cliches.

You know the drill – the air raid siren, a gas mask in the shelter, Vera Lynn, a Spitfire, stumbling in the blackout, a tearful goodbye, the drone of night time bombers and clack of ack-ack guns, dancing to Glenn Miller and St.Paul’s in the moonlight.

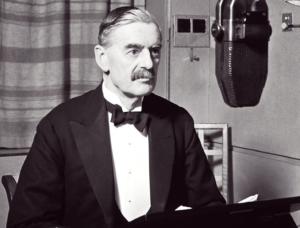

The classic opener is the family gathering round the bakelite radio on September 3rd, 1939 as Chamberlain intones that “this country is at war”:

I am speaking to you from the Cabinet Room at 10, Downing Street.

This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final Note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 0’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p03tpdz7

Throw in rationing, a quick romance, some shoulder pads and foreign uniforms, the all-clear and an ARP helmet and you’ve got the whole London Blitz home front thing down.

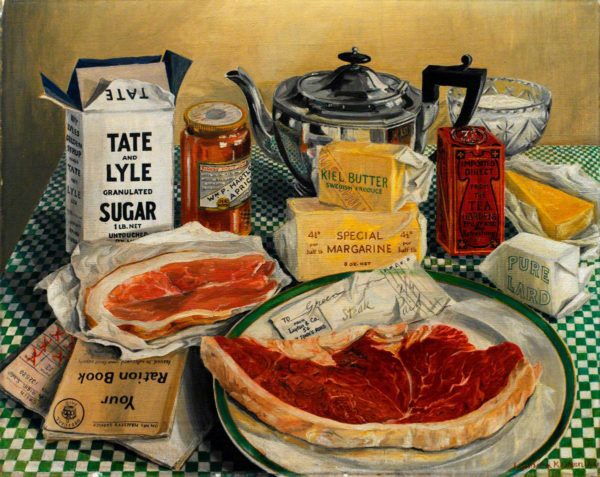

One of the ways Kate Atkinson anchors her novel Transcription is through a running theme of food. And of course that makes perfect sense. The novel switches back and forth between 1940 – time of high food anxiety – food queues, worrying about coupons, deprivation and the constant fear of what would happen if… and post war 1950 – with austerity measures in place and a county still in the grip of scarcity and rationing. A pre-occupation with food and eating makes sense.

The other method she uses is to weave in the names of historical figures and events to provide a backcloth on which to present her story. Atkinson is really good at this. Combine that with her wonderful ability to turn a felicitous phrase – well, there’s a good reason I always look forward to her next novel.

As a baby boom child of that era it all make sense to me. Growing up, everything was either before the war, or during the war, and then, after the war. 1939-1945 was the defining time of my parents’ lives. And many of those family conversations centered on food – where to get it; how much it cost; could we afford it; what was a good substitute; how could you grow it; how to preserve it and was it good for you. And most of all – never to waste it. Waste was wicked.

This is the second post provoked by Kate Atkinson’s terrific novel Transcription about spies and spying, deception and delusion, double lives and double cross in wartime and postwar London. You can read the other one here.

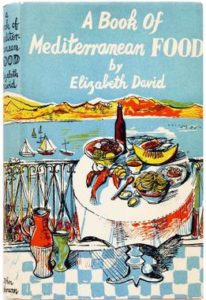

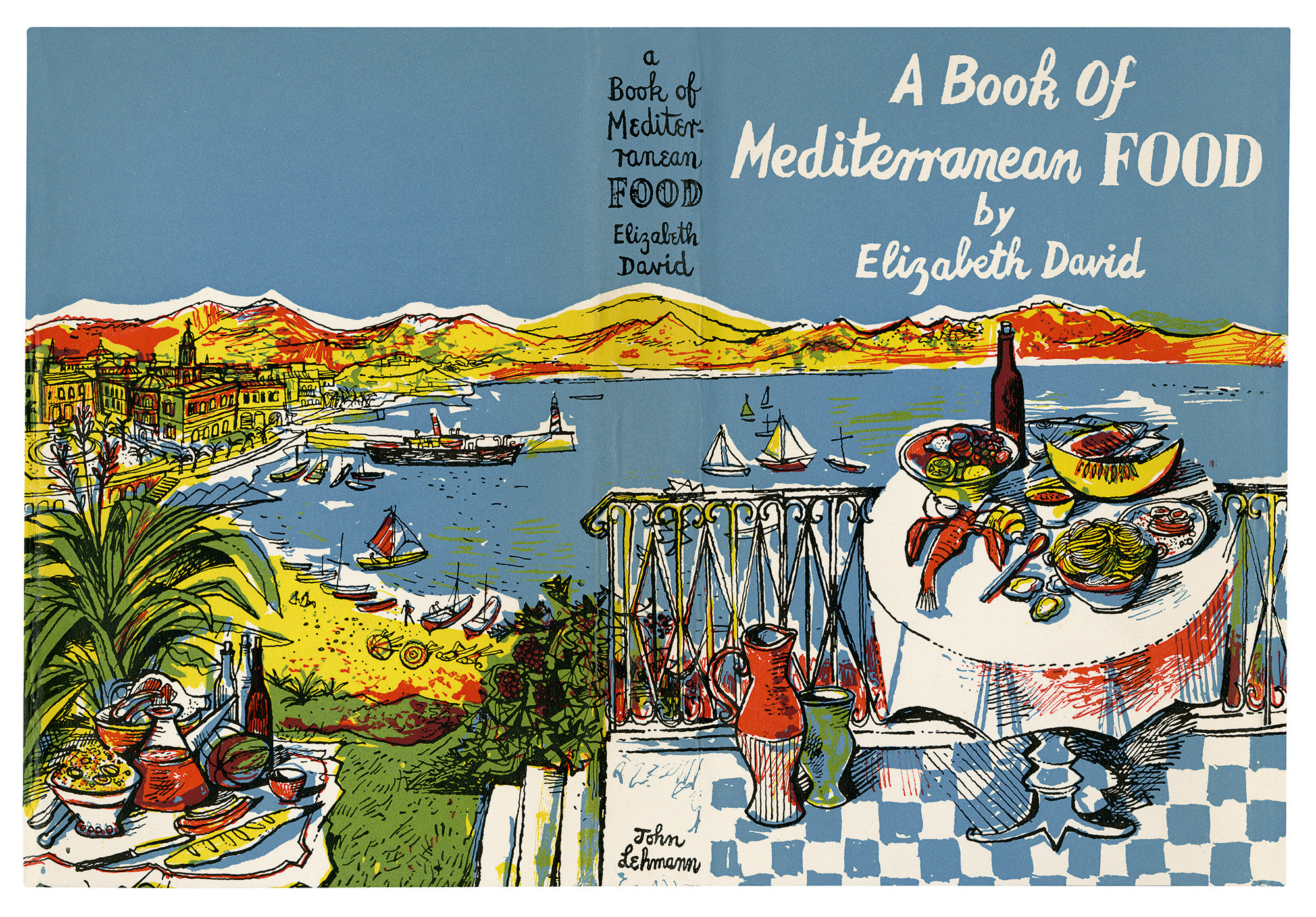

Early in the novel our protagonist – Juliet Armstrong – eats a pale limp sandwich and the contrast is drawn with a book she had recently bought – Elizabeth David ‘s A Book of Mediterranean Food. It’s 1950.

A hopeful purchase. The only olive oil she could find was sold in her local chemist in a small bottle. ‘For softening earwax?’ he asked when she handed over her money.

Olive oil was something you bought at Boots the Chemist. Or, in my mother’s case, the health food store on Fleet Street, Swindon. That store along with others of its kind sold all kind of strange potions and supplements as well as wholemeal flour; yoghurt at a time when it was unavailable anywhere else; spaghetti from Italy in long blue paper packets; muesli and nut butters before they were fashionable. It had that distinctive health food store smell of fennel seeds, dry yeast and lentils.

Olive oil was something you bought at Boots the Chemist. Or, in my mother’s case, the health food store on Fleet Street, Swindon. That store along with others of its kind sold all kind of strange potions and supplements as well as wholemeal flour; yoghurt at a time when it was unavailable anywhere else; spaghetti from Italy in long blue paper packets; muesli and nut butters before they were fashionable. It had that distinctive health food store smell of fennel seeds, dry yeast and lentils.

The olive oil was for external use only – a salve for chilblains or aches and pains. It was not for the Sunday salad – Heinz Salad Cream was for that . Nor was it for cooking – fried food was not good for you. And the same with garlic.

Health savvy people knew garlic was beneficial but didn’t cook with it. They bought garlic perles encased in glycerin so as not to smell and give offense.

The war made my mother into a hoarder and forager (blackberries, hazelnuts, rosehips, field mushrooms, dandelions, nettles, elderberries) compounding a natural tendency to frugality borne of a childhood where she remembered deprivation and a longing to eat fresh fruit.

It established a lifetime habit of buying in bulk and – every post-war January when Seville oranges were in the shops – marmalade making. My brother and I agreed that the batch she made in the last year of her life was probably her best ever.

A decision to become a vegetarian at the age of 15 added another layer of emotional intensity to the focus on nutrition and food. Waste was “wicked’ and plates should be finished. Food should be home-grown, stone-ground, wholemeal, organic and “natural” whenever possible. Brown was generally good. White generally bad. Composting was righteous. And nothing thrown away.

That juxtaposition of a limp sandwich and Elizabeth David is a deft piece of scene setting. David’s groundbreaking book burst on the British food scene in 1950 like a glorious day of warm sunshine in a dismal December. Before there was Nigella Lawson and Jamie Oliver and all the other celebrity Brit cooks, there was Elizabeth David. Juliet buys David’s first book although there is no evidence that she has much interest in cooking or the Mediterranean. It’s a stand-in for a hope of better times ahead.

Ritzkrieg v. Rationing

Throughout the novel – which is about spies, loyalty, betrayal, deception and delusion (This England. Is it worth fighting for?) – there’s a running contrast between Juliet’s usual unappetizing fare and the extravagant meals, drinks, restaurants and night clubs that her work and work companions occasionally bring. It’s feast or famine; fine dining or frugality.

The contrast is between the drab and dreary and bursts of extravagant luxury.

On the first page of 1950 Juliet has dined with an architect who was “rebuilding post-war London”. “All on your own?” she has asked, rather unkindly.

They dine at the Belle Meunière on the house specialties – Viande de boeuf Diane and Crêpe Suzette.

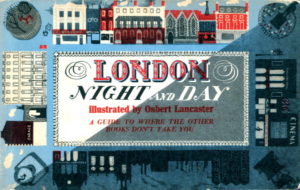

In London Night and Day, 1951, a reviewer reported on the restaurant:

‘Décor near modern white walls, pink lights, pink carpets. Bar at the back. Doorman. Waiters white-jacketed. Very good food cooked personally for you A la carte about 15s. Personal service from proprietors Mario and Gaspar.’

It was at 5, Charlotte Street and there’s still a restaurant there – the Côte Brasserie – still offering French food. If you want to call for a reservation at the Belle Meunière, just step into the TARDIS and dial Mus 4975

Juliet takes a salad cream and egg sandwich to eat in Cavendish Square Gardens and eats prewar and postwar (no Italian cheese and no Italian bread) at a Fitzrovian coffee bar Atkinson calls Moretti’s. As she drinks the1950 bitter, grainy Turkish coffee – only made palatable by sugar – she remembers the prewar Viennese coffee with whipped cream and cinnamon.

In 1940 our protagonist is at a Lyons Corner House on Lower Regent Street (this must be the one on that was on the corner of Coventry and Rupert streets close to Piccadilly – ham salad and boiled potatoes and – imagining wartime deprivation ahead – indulging in tea and two iced buns.

With MI5 setting up shop in Wormwood Scrubs prison, we are told of debutante recruits with picnic hampers nibbling on chicken drumsticks.

With her debutante, debutante-dissing, new friend Clarissa, Juliet has quite the night life – often ending the evening with coffee from a late night stall or straight into a Lyons for a breakfast of porridge, bacon and fried bread, toast and marmalade and a pot of tea. All for 1s 6d. Bargain!

The Café de Paris

By contrast there’s gimlets and gossip at the Café de Paris – a night club on Coventry Street, opened in 1924 and made famous by the famous including the Prince of Wales, the Aga Khan and Cole Porter.

The dance-floor was originally designed to resemble the ballroom on the Titanic. In the early years of the war it was a popular – and less exclusive – night spot for the stylish who could afford it. The dance floor was several levels underground and party-goers thought it a safe and more appealing alternative to taking your chances at home or a night in a shelter.

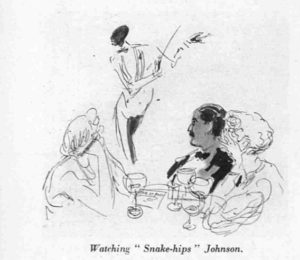

The clubs’s resident band was the West Indian Orchestra led by Kenrick Johnson. He was also a regular on the BBC giving the nation a taste of swing music. He was at the club on Saturday March 9th, 1941 and just getting started when the air raid siren cranked out a warning.

The band and the crowd were blasé about the danger. The club took two direct hits and a 50 kg high-explosive bomb entered the ventilation shaft and went down into the very heart of the club. There was a blinding blue flash and the bomb exploded on the dance floor.

At least 34 people died and dozens more were seriously injured. Ken Johnson was decapitated.

The Café de Paris remained closed for the rest of the war but reopened in 1948. It is still open today. Our fictional heroine Juliet loses a friend in the incident and later, at the BBC, works with a man who lost a leg there.

In the real world – Johnson was the best-known victim. He had been born in British Guiana and travelled alone to the UK on the SS Nickerie in 1929. He was fourteen. His parents hoped he would become a doctor and they wanted him to have a British education. Ken however, was more interested in music and dance. After leaving school he became a professional swing musician earning the nickname Snakehips for his moves and agility.

Here’s a taste of Ken Johnson and his band. They were in demand at fashionable London venues, including the Café de Paris.

But away from the glamor of the West End, Juliet eats gamy hash in the MI5 canteen at the Scrubs, biscuits at Dolphin Square and drinks tea. Tea everywhere.

At one point she has to make a decision about whether to eat the Ryvita in her handbag. Gourmet decisions!

She’s invited to a drinks party at the Admiralty by her boss who points out the politicians – Maurice Hankey, Leslie Hore-Belisha and Lord Halifax. This is pre-Dunkirk 1940.

She is taken to dinner at L’Escargot on Greek Street – still going strong as London’s oldest and most celebrated French Restaurant. It was founded by Georges Gaudin in 1896 at the end of Greek Street and was originally called Le Bienvenue. Gaudin became famous for his snails and when he moved to larger premises at 48 Greek Street in 1927, his customers urged him to rename his restaurant L’Escargot after his most popular dish. He kept a snail farm in the basement.

Charles De Gaulle and his Free French cohort were frequent diners during the war.

L’Etoile gets a mention but its now no longer fizzing with Parisian charm and old world glamor. Established in 1896, L’Etoile is now closed. But Juliet was there.

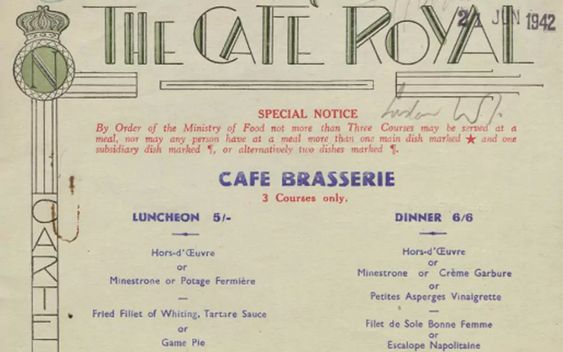

One character anticipates missing his Sunday roast as the war closes in, and Juliet goes to the the Café Royal on Regent Street. This was before Food Minister Lord Woolton took measures to curb excessive consumption at leading hotels and restaurants. From June 1942 on, they were only allowed to serve a maximum of three courses to each guest during one sitting. Fish, game and poultry could be banned on certain days of the week and five shillings became the maximum charge for a meal. That order is printed in red at the top of the menu.

Juliet has dinner with her boss Perry at the Bon Viveur in Shepherd Market, Mayfair – chicken in a white sauce some kind of marmalade pudding and an excellent Pouilly. They toast “To victory!” This is actually her first fine dining experience and comes after a chilly trip to the country where otter watching and hare boxing were the key entertainment. The regurgitation habits of owls provides a romantically disappointing topic of conversation

She has tea and cakes at the Dolphin Square restaurant.

And shepherd’s pie gets a mention as one of her favorite dishes.

Juliet remembers the boiled cabbage and pigs trotters of her Russian emigre neighbors in Kentish Town as she heads in an assumed identity for a rendezvous with fascist sympathizers at the Russian Tea Room in Knightsbridge. This was owned by Anna Wolkoff’s family and was in fact a hotbed and meeting place for the far right.

Pierogi, blini, and stroganoff are on the menu as well as verushka, which our heroine hears as verucca.

At a follow-up meeting, one of the well-heeled fascist sympathizers bites into a maid of honor.

At the house there’s an odd phone conversation concerning pork chops which is possibly anti-semitic code and Juliet spots an envelope addressed to William Joyce.

The pampered rich and well-connected could still eat well In wartime.

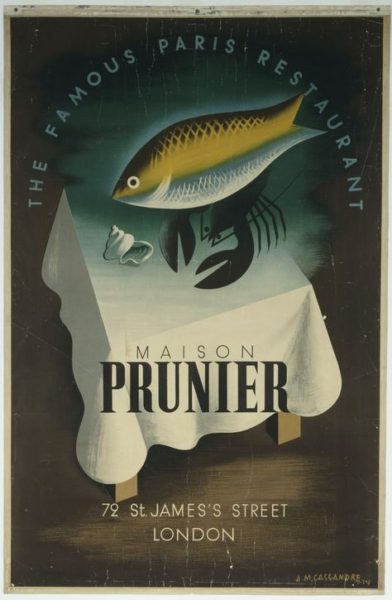

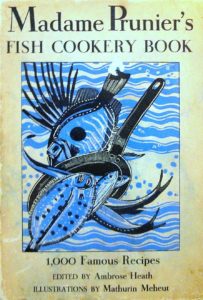

Lobster was not rationed, but expensive and hard to get. Juliet eats it at Prunier’s on St. James’s Street.

Oh, Madame Prunier, you give us fishes which we wouldn’t dream of eating anywhere; you call them by a funny French name, and we all adore them!

Simone Prunier quotes this remark from an English client in her cook book of 1938. It rather sums up the formerly prevalent British ambivalence toward French food and all things foreign – it tastes and smells good, but … frogs and snails!

Back to more staid English fare. Juliet has a pot of tea and a slice of walnut cake at Fuller’s in the Strand before going to see Rebecca at the Curzon Cinema in Mayfair.

She’s invited to a swanky party at a splendid house on Pall Mall – a glittering gathering of fascist sympathizers. There was a lavish spread of food – “no signs of rationing here” – and she is served a purple cocktail. “I believe it’s called an Aviation” Juliet says as she declines a second.

Juliet has coffee and scones with Mrs Scaife as they discuss espionage on behalf of the gestapo,

She has cocktails at the Rivoli Bar at the Ritz and roast beef at Simpson’s on the Strand.

At the Russian Tea Room she has goulash which she hears as “ghoulish” and, as she tells Perry afterward, “It was rather. I dread to think what animal was in it; it tasted quite zoological.”

And tea, of course. Cups of tea punctuate the timeline of the plot – with and without biscuits. For refreshment, for recovery “we’ve had rather a shock”, and well, just because. Tea at home, tea at work, and tea in teashops.

And when Perry invites her on a second outing she wisely prepares a thermos and sandwiches.

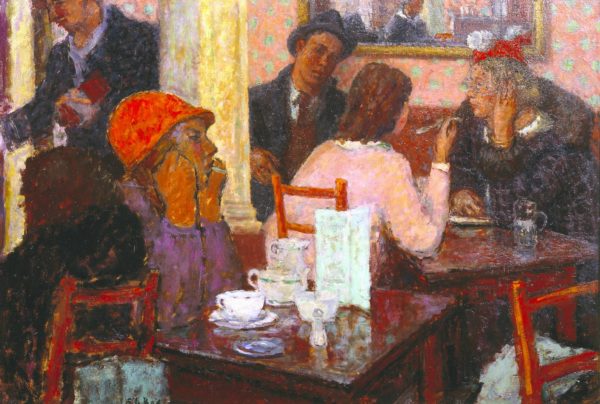

Café Scene 1939

Painted from drawings made in London tea shops, probably Lyons.

A lunch at Prunier ‘s after a success – not lobster this time but Poularde au Riz Suprême made with chicken that “had come up that morning on the milk train from Hampshire.” And Juliet laughs because she imagines “the platform of some sleepy halt crowded with chickens fussing and clucking like commuters waiting.”

And then downmarket to bread and butter and a tin of spaghetti.

In preparation for a guest – and because it’s on an MI5 account – Juliet shops in Harrods Food Hall and buys bread, butter, ham sliced off the bone, a thick wedge of cheddar, a half dozen eggs, a jar of pickled onions and a bunch of grapes.

One character in the novel – Hartley – indulges in good food and over indulges in alcohol. He

reeked of garlic, unpleasant in the small space of a black cab. He had always possessed some outlandish tastes in food gherkins and garlic, stinking cheeses and once, she had gone to his cell in the Scrubs for something and had found what looked like a glass jar of what looked like tentacles.”Squid,” he explains “came in on a flight from Lisbon.”

She drew the line at this fish

There’s a particularly unappetizing meal in the BBC cafeteria:

It wasn’t Friday and yet it was fish, or at least an attempt at fish. Small irregular shapes had been crumbed up in something offensively orange and them baked in an oven. The fish inside the orange crumb was grey and gelatinous … Over boiled potatoes and tinned peas completed the assemblage.

And in a moment of self examination Juliet wonders about the meaning of all this food:

….she had eaten her way through grief, she had eaten her way through what had passed for love, she had eaten her way through the war (when she could). She sometimes wondered if there was some emptiness inside that she was trying to fill, but, really she suspected that she was just hungry a lot. She drew the line at this fish though.

The BBC tea trolley clatters toward her like a steam engine. There’s a pot of tea to wash down two aspirin. And the Harrods leftovers are the makings of an omelette and the grapes have a second lease on life as a hospital gift to a dying colleague.

There’s cocoa, and Camp coffee with two sugars and Carnation milk. And when the tea girl brings the tea, Juliet and her producer eschew the plain biscuits in favor of the fruitcake that his wife had made.

There’s cocoa, and Camp coffee with two sugars and Carnation milk. And when the tea girl brings the tea, Juliet and her producer eschew the plain biscuits in favor of the fruitcake that his wife had made.

Drinks at the Savoy and Raie au Buerre Noisette and a Tarte aux Pruneaux and a whole bottle of Burgundy at the Mirabelle in Mayfair.

Orson Wells and Winston Churchill were regulars and the restaurant attracted the rich and famous into the 21st century. Tim Zagat of restaurant review fame was once ejected by the owner because the guide had given a bad review to one his other restaurants.

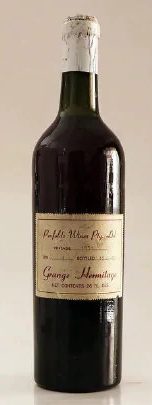

In 2012, the Mirabelle made the celebrity news when a waiter refused to replace a £3,500 bottle of Penfolds Grange Hermitage 1964 for actor Russell Crowe who said that it was corked.

Who said Australian wines are cheap? The waiter finally relented and replaced the bottle.

As Juliet tracks down the past that seems to be tracking her, there’s more fish – in Brighton this time – with chips, peas, bread and butter eaten at a table covered in gingham cloth in a cafe overlooking the crashing rattling waves on the English channel on a blustery sunny day.

“Finished with that?” the waitress asked, grabbing her plate

“Yes, thank you, it was delicious.” the waitress, a woman in her late forties wrinkled her nose slightly. Juliet supposed “delicious’ was the kind of word that spoiled middle-class women down from London employed….

“More tea?” the waitress asked, hefting an enormous brown enameled teapot in Juliet’s direction.

“Yes, please,” Juliet said. The tea was horrendous, thick and sludgy brown like the river she had left behind in London. “Lovely.”

She rides in a taxi with a half empty bottle of chateau petit-village 1943 excellent vintage jammed between the seats. “Pierre Auguste at Le Chatelaine gets it for me.,” her companion explains.

She eats a rather questionable corned beef sandwich amidst the usual dilapidated clientele of a north London pub and then tea in Finchley and breakfast with more tea with a plate of toast with real butter. Her host explains, “Annabelle’s sister lives in the country. I’m afraid we finished the last of the marmalade weeks ago”

A complaint about the work tea features in a rapidly invented cover-up story and there’s mutton pie for lunch in Dolphin Square . “Although I don’t know how they can call it mutton. It’s not a meat that’s even seen a sheep.”

There’s a seduction scene with a tall detective who shares a large bottle of beer and a 1950 sandwich eaten on the steps of the National Gallery which – along with drinking whiskey with a mysterious man in an astrakhan collar – brings us back full circle:

The sandwich contained a depressing fish paste filling that would probably have horrified Elizabeth David and quite rightly too.

Atkinson knows just how to mine a memory and nostalgia with just the right amount of period detail and name dropping and she manages to do with without being clumsy and heavy handed. Real historical figures get passing mentions – politicians, actors, BBC announcers – as do the events. Ships sink, characters drown, the army is rescued from Dunkirk, invasion looms and nations fall – Hitler was collecting countries like stamps. And later, Klaus Fuchs is put on trial – Fuchs is fucked.

When Elizabeth David wrote her first book she wanted her readers to escape from “the frustration of buying the weekly rations” and “to read about real food cooked with wine and oil, eggs and butter and cream, and dishes richly flavoured with onions, garlic, herbs and brightly coloured southern vegetables”. This, she conceded, might be “over-picturesque for every day; but then who wants to eat the same food every day?”

When Elizabeth David wrote her first book she wanted her readers to escape from “the frustration of buying the weekly rations” and “to read about real food cooked with wine and oil, eggs and butter and cream, and dishes richly flavoured with onions, garlic, herbs and brightly coloured southern vegetables”. This, she conceded, might be “over-picturesque for every day; but then who wants to eat the same food every day?”

David had spent the war years in the Mediterranean – France, Greece and Egypt – where fresh ingredients for good food were readily available and the sun shone. Returning to the food of post-war London was a dispiriting experience.

There was flour and water soup seasoned solely with pepper; bread and gristle rissoles; dehydrated onions and carrots; corned beef toad in the hole. I need not go on.

She issued her rallying cry in indignation at the drab miseries of the national diet. She offered tantalizing recipes for dishes like moules marinières and kokkoretsi, bocconcini, bouillabaisse and bourride, lièvre à la royale, paella Valenciana and boeuf en daube. She encouraged her readers to make shopping expeditions to the region of Tottenham Court Road to “buy Greek cheese and Calamata olives, Tahina paste from the Middle East, little birds preserved in oil from Cyprus, stuffed vine leaves from Turkey, Spanish sausages, Egyptian brown beans, even occasionally Neapolitan Mozzarella cheese, and honey from Mount Hymettus.”

All very well if you lived in London and could afford it.

The genesis of the book was a bleak stay with a lover in a hotel in Ross-on-Wye. Stranded by a blizzard and disgusted by the food, she started to write the antidote to joyless meals and her words became her groundbreaking A Book of Mediterranean Food.

Hardly knowing what I was doing … I sat down and started to work out an agonized craving for the sun and a furious revolt against that terrible cheerless, heartless food by writing down descriptions of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cooking. Even to write words like apricot, olives and butter, rice and lemons, oil and almonds, produced assuagement. Later I came to realize that in the England of 1947, those were dirty words I was putting down.

She had already been writing articles for magazines and they had been well received. Her book struck a chord with a rationing weary middle class British public who were captivated by the lush descriptions of food and dishes beyond their imagination. Her work tempted people who had never tasted or thought of what are now modern culinary staples such as garlic, olive oil, Parmesan cheese, peppers, pasta. Her recipes called for exotic ingredients like basil, aubergines and saffron and she tweaked and tempted the imaginations of those who could not yet find a way to experience these delicacies first hand. She created a yearning that time would fulfill.

This is how David’s biographer Artemis Cooper concludes her Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry:

This is how David’s biographer Artemis Cooper concludes her Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry:

David was the best writer on food and drink this country has ever produced. When she began writing in the 1950s, the British scarcely noticed what was on their plates at all, which was perhaps just as well. Her books and articles persuaded her readers that food was one of life’s great pleasures, and that cooking should not be a drudgery but an exciting and creative act. In doing so she inspired a whole generation not only to cook, but to think about food in an entirely different way.

Let me just end with this one thought: Kate Atkinson is brilliant and writes a damned good book.

This is so interesting, thank you! I love food in books, it’s wonderful social history. I haven’t read Transcription yet, but will

A very interesting read Josie. I’d forgotten all about Ham salad with boiled potatoes and the fact that olive oil was only ever seen in chemists in a little bottle. I listened to the Ken Johnson medley whilst reading – very enjoyable!

such an informative mostly Elizabeth STORY.

Thanks John – it was fun to write and delve into. And I really admire Atkinson’s ability to ground a story in time as well as the wonderful way she can turn a phrase.

Such an evocative piece – thank you.