This post is in answer to the question “Operation Pied Piper: What were they thinking?” At least in terms of the evacuation scheme. The choice of code-name remains ambiguous.

It begins with a little history.

Napoleon

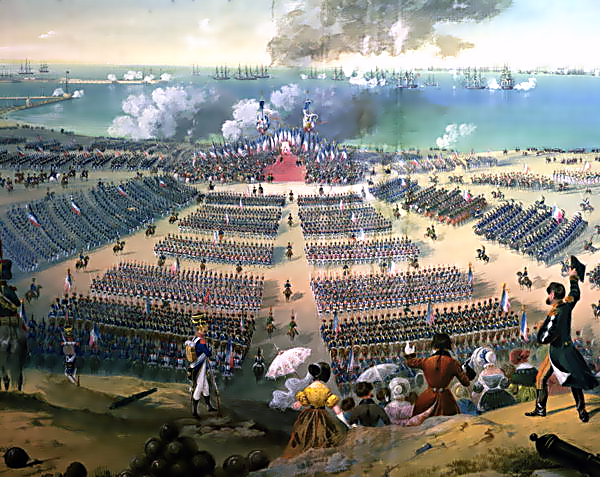

In the first years of the 19th century, Napoleon made no secret of his intention to invade Britain, destroy the monarchy and take over Britain’s imperial possessions. In 1803 he massed a huge ‘Army of England’ at the channel ports of Calais and Boulogne – over 200,000 men with 2,000 ships.

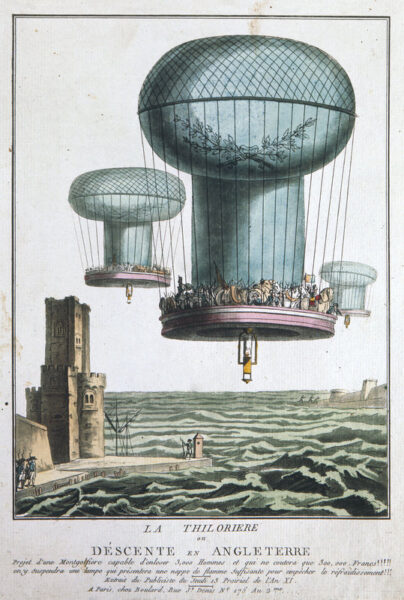

Other and highly imaginative invasion methods were also considered. They included building a tunnel under the Channel and a fantastical fleet of air balloons capable of carrying troops, weaponry, and horses.

One can only imagine such a fleet of armor-carrying balloons being blown off course rather like the Spanish Armada of 1588.

Britain took the invasion threat seriously, expanding the military and building coastal defenses in Sussex, Kent, Essex, and Suffolk. King George III and the government developed detailed plans for a vigorous response. The king would lead the armed defense from Chelmsford if the attack came in Essex and from Dartford if the attack came in Kent.

In addition to the coastal fortifications, some places in southern England developed civilian evacuation plans in the event of an invasion. In the village of Nonington on the road between Dover and Canterbury plans were drawn up for the civilian evacuation of local villages.

In the end, they were not needed as Napoleon’s invasion plan foundered in 1805.

The French navy failed to control the Channel after naval defeats at Cape Finisterre and Trafalgar and Napoleon turned his attention elsewhere.

Remember Scarborough!

Just over a hundred years later, France was an ally and Britain was at war with Germany. In the early months of WW1, high-ranking German naval and military personnel argued for an aerial campaign against Britain. One proponent – Konteradmiral Paul Behncke (1866-1937) – believed that bombing London, its docks, and the Admiralty building in Whitehall would cause civilian panic and possibly render Britain incapable of pursuing the war.

Just over a hundred years later, France was an ally and Britain was at war with Germany. In the early months of WW1, high-ranking German naval and military personnel argued for an aerial campaign against Britain. One proponent – Konteradmiral Paul Behncke (1866-1937) – believed that bombing London, its docks, and the Admiralty building in Whitehall would cause civilian panic and possibly render Britain incapable of pursuing the war.

The Kaiser – Wilhelm II – was reluctant to give the go-ahead to the bombing of London. Perhaps it was his family connections. He and his cousin King George V were the grandchildren of Queen Victoria.

About 8 am on Wednesday, December 16th, 1914, German battlecruisers fired on the undefended town of Scarborough on the Yorkshire coast before cruising north to attack Whitby. Further up the coast, German warships attacked Hartlepool, which had a garrison and three naval guns.

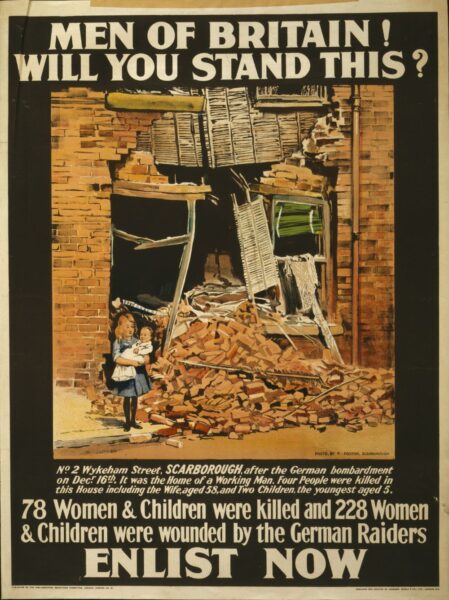

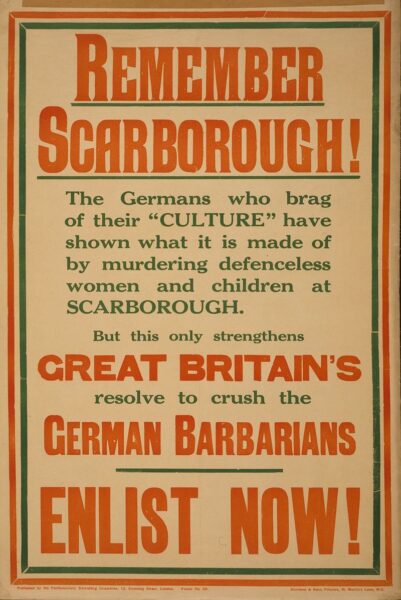

Seventeen people were killed in Scarborough that morning and two more died of wounds later. More than 80 were seriously wounded. In the three towns 137 people died, the majority in Hartlepool. It was the Scarborough attack, however, that most shocked the country and served to galvanize anti-German outrage. “Remember Scarborough!” became a rallying cry for recruitment.

Seventeen people were killed in Scarborough that morning and two more died of wounds later. More than 80 were seriously wounded. In the three towns 137 people died, the majority in Hartlepool. It was the Scarborough attack, however, that most shocked the country and served to galvanize anti-German outrage. “Remember Scarborough!” became a rallying cry for recruitment.

Over 500 high explosive shells fell in Scarborough in about a 20 minute period that morning. The news quickly spread with stories of the dead and wounded.

Of shop porter Leonard Ellis who was killed as he opened the door of Clare & Hunt’s chemist on South Street.

Of postman Alfred Beal killed delivering letters.

Of the housemaid Edith Crosby as she prepared breakfast.

Of 14-month John Shields Ryalls,

Of Alice Duffield who had gone out to look for her husband after he went to use a telephone. She died on the steps of the Granville Hotel when a shrapnel shell exploded directly above her. The last hit was 15-year-old Boy Scout George Taylor, on his way to buy a newspaper.

British recruiting poster picturing damage from German naval artillery to a civilian house was captioned “No 2 Wykeham Street, Scarborough….four people were killed in this house including the wife…and two children, the youngest aged 5.”

Winston Churchill the First Lord of the Admiralty seized on the propaganda potential and dubbed the German Navy “baby-killers”.

Death from the Skies

The first aerial bomb to fall on British soil, was dropped on Dover by a seaplane on Christmas Eve 1914. The Kaiser gave conditional approval for Zeppelin raids (Germany actually used both Zeppelin and Schütte-Lanz airships) beginning on January 10th, 1915. London was excluded as a target until May, and the first raid on the capital was in May.

In 1915 and 1916 there were 59 German air raids – 8 of them on London – 42 by airships and 17 by planes. Newly developed high explosive ammunition blunted the effect of the airships by giving the defenders the capacity to ignite the hydrogen in the Zeppelins.

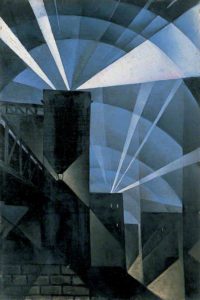

Airship attacks continued but bomber plane attacks predominated. The first daylight raid on London was by Gotha bombers in June 1917. Aircraft losses led to a switch to night raids

The German aerial bombing campaign killed and injured thousands and caused considerable material damage to London and coastal towns. They did not however break morale and actually fueled demands for reprisals.

But the idea of death from the air and of the civilian population under dire threat was established. You were no longer safe just because you were away from the front line.

Hope and Fear: The Politics of the 1930s

Now that the hideous air war has cast the shadow of its wings over the harassed civilisation of the 20th century, no one can pretend that by any measures which we could take it would be possible to give absolute protection against an aggressor dropping bombs in this island and killing a great many unarmed men, women and children. Winston Churchill 1934 https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1934/mar/08/air-estimates-1934#S5CV0286P0_19340308_HOC_239

British politics of the 1930s were a mix of hope and fear. WW1 was still a living memory and the trauma of those years could be easily summoned to support a never again pacifist agenda, support for a policy of appeasement, and preparations for civilian safety in the event of aerial bombardment.

In the early decades of the C20th London grew at a rapid rate. It was the largest city in the world as well as the seat of government for the UK and the sprawling British empire. The City of London was the world’s financial capital and more than half the world’s international trade was financed through London companies.

Most politicians and civil servants would remember the WW1 bombing of London and press reports and newsreels brought the dangers of air raids home to civilians. The Italian poison gas attacks on Abyssinia, the 1937-38 Japanese bombing of Shanghai, and the 1937 German bombing of Guernica made the plight of civilians under air attack familiar and horrifying.

Government accounts overestimated the casualties of the next war with dire predictions of how many Londoners would die. Fire was the big fear of the Air Raid Precaution (A.R.P.) planners and mass hysteria and public panic and disorder were anticipated. In a plan to manage the disorder the government consulted crowd control experts from India. Troops were readied to be deployed for riot control.

People and the government were primed to fear the worst should war come. It made sense then to prepare to protect the most vulnerable with a plan for mass evacuation.

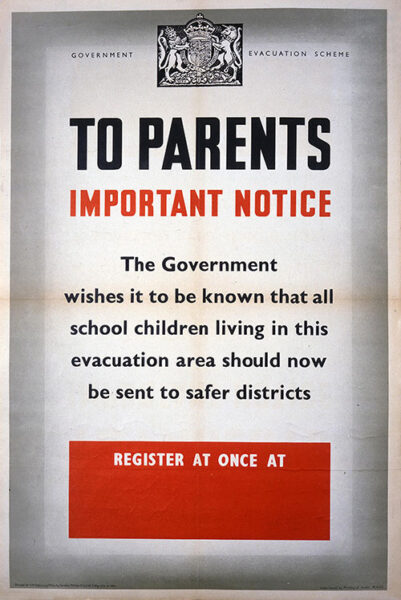

Operation Pied Piper was the plan to evacuate vulnerable civilians from cities and high-risk areas. The country was divided into three zones: Evacuation, Neutral, and Reception. The Evacuation areas included the big cities; Reception areas were rural areas; Neutral areas were places that would neither send nor receive evacuees.

Those to be evacuated were divided into four groups all deemed to be non-essential to war work: school-age children; the infirm; pregnant women; and mothers with babies or pre-school-age children who would be evacuated together.

The government evacuation scheme was developed in the summer of 1938 and was further fleshed out by incorporating the detailed plans of the London County Council (LCC). By the summer of 1939, the LCC had registered thousands of potential evacuees and co-opted the schools as partners. It requisitioned busses and trains in preparation. Britain was preparing for the worst.

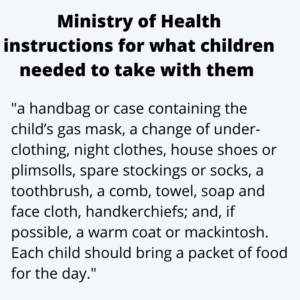

On Thursday, August 31st – three days before Britain declared war – and evacuation was ordered for the next day. Families prepared their children and – to the best of their ability – supplied them with the required items of clothing, food for the journey, and their gas masks.

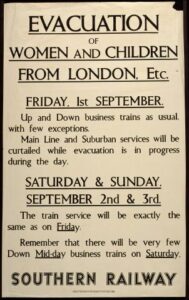

On Friday, September 1st, children began assembling in their schools, and parents said goodbye. Operation Pied Piper was launched.

It was a huge logistical enterprise. In London alone, there were 1589 assembly points. Trains steamed out of the city’s main terminal stations every nine minutes for nine hours. It involved teachers, rail workers, officials from the local authorities, and 17,000 members of the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) who did the practical work of looking after the children and providing refreshments.

In the first three days, 1.5 million people were evacuated including 673,000 unaccompanied children from England alone.

Parents deposited their children at the assembly points and handed them over into the care of teachers and WVS volunteers. Every child was pinned with a luggage label on which was their name, school, and local evacuation authority.

Operation Pied Piper was one of the most radical social engineering projects ever conceived and it is no wonder that right from the start it triggered widespread discussion, interest, and concern. It affected the lives of millions and left an enduring impact on the British psyche and cultural memory. It was controversial from the start. On all that – more anon.

This post provides a fascinating historical overview of Operation Pied Piper and its significance during World War II. It’s intriguing to see how such a massive evacuation plan was organized and executed in response to the threat of aerial bombardment.

What do you think was the most challenging aspect of implementing Operation Pied Piper, both logistically and emotionally, for the families and authorities involved?

JARLOX NS´s last blog post ..Qatar and Philippines Ink Nine Agreements to Boost Trade and Collaboration

Josie…it’s Eunice Price. Please email me!

Like many children he was not happy with the family that took them in though he was lucky to be with his older brother. They went home at Christmas and persuaded their mother not to send them back!

Thanks for the additional details. That going back after the months of the sitzkrieg was a familiar pattern. Many paid for the decision dearly. But the facts are that children and many adults shuttled back and forth from the big cities quite often as circumstances and the perception of risk changed. And the number of changes of address during the war years was extraordinary.

That’s fascinating. As a little boy my dad was evacuated from London with his older brother and this gives me so much background and context for that event. He will always remember that his cap blew away when he leaned out to wave goodbye to his mother. Thanks for such a detailed post!

The hat – what a great detail! Would love to know more of their story.

I still find it extraordinary that between the Wright Brothers flights in 1903 it was only fourteen years to the Gotha bombing raids (and ‘only’ half a century later humans landing on the moon). And yet it took nearly two hundred years for a Channel Tunnel to become a reality… Anyway, good documentation in a relatively short post!

I suppose that if you consider balloons as part of the trajectory of flight then the timeline lengthens. I suppose the tunnel was always a simple idea but more complex from an engineering standpoint. And then of course – the politics! (All those centuries of enmity and now you’re building a way in?)

Apparently, Thatcher’s preference was for a road tunnel, not the current rail service. It’s thought that she wanted a road tunnel because cars “represented freedom and individualism”.

Why is it I’m not surprised about Thatcher’s preference for a road tunnel? All of a part with her denying there was such a thing as Society, which then would then logically make Socialism a pointless philosophy…

Thatcher – like Reagan – so much to answer for.

Apologies — I don’t know how that wrong link appeared, but it was supposed to be about the ten best British films about WWII. In any case, I mentioned the two I’ve seen and liked, so I’ll let it go at that.

No apology needed. Let’s take advantage of the accident and enjoy!

Very interesting. Have you seen any of these films related to the subject of your post? I’ve seen only two: MRS. MINIVER and WHISKEY GALORE, both of which I highly recommend.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i3dRtKT04sw&w=789&h=592%5D

Sorry – somehow, the wrong clip appeared in my previous comment. I’ll try to check it out.

Keep up carrying on with the wartime posts… so much part of our histories.Gills house in Scarborough was bombed in the first world war…you’d never think she was that old….We all have stories that should be recorded and told. Well done anon.

I’ve only got about four more. But I need to edit them down – a lot. Am on to the fiction and the playing cards next. Thanks for the encouragement.