The sandwich was no comfort, it was a pale limp thing a long way from the déjeuner sur l’herbe of her imagination. . . . Recently she had bought a new book, by Elizabeth David — A Book of Mediterranean Food. A hopeful purchase. The only olive oil she could find was sold in her local chemist in a small bottle. ‘For softening earwax?’ he asked when she handed over her money. There was a better life somewhere, Juliet supposed, if only she could be bothered to find it.”- Kate Atkinson, Transcription.

(I love that little last line nod to Winnie the Pooh.)

The ‘she’ is Juliet Armstrong in 1950. who – we learn in the first chapter – was run over in 1981 crossing Wigmore Street after listening to Shostakovitch in Wigmore Hall. “‘This England’, she murmured” as she lies dying on the street.

The world of 1981 is a confusing place. And as far as this novel is concerned: “Twas ever thus.

The Russians had been their enemies and then they were their allies, and then they were enemies again. The Germans the same — the great enemy, the worst of all of them, and now they were our friends, one of the mainstays of Europe. It was all such a waste of breath. War and peace. Peace and war. It would go on forever without end.

Transcription is a terrific novel. After that initial chapter, the action switches forth and back between the drab austerity of London of 1950 and the anxious, uncertain, paranoid and fearful London of early 1940.

Juliet is recruited by MI5 straight from school. “They are looking for girls like you” her headmistress had said, but without without specifying what sort that was.

And so Juliet is drawn into a world of fevered espionage.

There are secrets and invisible ink, multiple identities, bodies to be disposed of and nothing is quite what it seems as loyalties and alliances are confused and confusing.

There’s double cross and hidden lives and someone whose first wife was said to have come to an unhappy end. There’s a classic pea-souper fog and a scene in a graveyard.

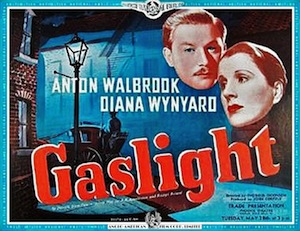

And just to make it all clear that this is a psychological thriller of deception and betrayal, we have cinema trips to see the great films of 1940 – the first Gaslight and Rebecca.

It’s a world of subterfuge, delusion, and uncertainty.

Nothing is as it seems. Part of Atkinson’s skill as a narrator is to provide the telling details that lend dimension and depth – that layer on meaning with a light touch.

Just in passing we hear that Juliet saw the 1949 production of Much Ado about Nothing at Stratford. Because of course she did.

What could be more apt than a play about deliberate deception – some malevolent, some benign, and the difficulty of knowing which is which? Who is wearing a mask? And what is behind the mask? Deceit as a means to an end, a social illusion.

Shakespeare’s play is a comedy and there’s a strong element of farce in the novel too, although the historical backdrop is grim. While Juliet is busy listening to the fascist sympathizers and transcribing their petty and malignant banality for MI5, the dominoes of Europe are falling before the Nazis. Invasion and defeat loom. Stormtroopers goose-stepping in a Whitehall victory parade is not a fascist fancy but a real possibility. The threat is existential.

And this is the great dilemma. Threats are real. Dictators and fascists exist. Countries are invaded. Ships are sunk. People are displaced, interned, forced to choose sides, killed. Lives are disrupted. And lost. Individual human behavior, however, is mostly an absurd delusion sliced with elements of farce.

In 1950 Juliet is working for the BBC in Schools programming situated across the road from the BBC mothership of Broadcasting House. And more opportunity for comedy and farce. (A live broadcast to schools goes out with a string of choice Anglo Saxon “You have to admire the rhythm I suppose” she comments.)

The novel pokes some fun at the earnest innocence of all that wholesome programming for children. But the BBC is a source of comfort too. There is a reference to Bruce Belfrage who carried on reading the 9’o’clock news when a bomb exploded in the building. It’s a quintessential example of keeping calm and carrying on.

Broadcasting House was first bombed just after 8 p.m. on 15th October 1940. A 500lb delayed-action high explosive destroyed the BBC switchboard. Staff tried to move the bomb but it exploded. Seven people were killed. Parts of the fifth and sixth floor frontage were blown into Portland Place and studios were demolished.

Bruce Belfrage was on duty as newsreader that night and had started his broadcast when the bomb went off. Listen to how he explains what happened and his reaction to the explosion that left him covered with dust. Interesting too, that the London blitz was not top of the news that night. It was a world war and the BBC was not a local outlet, although for part of 1940 it was at the epicenter of the action.

Then there’s that all-time Brit favorite radio nostalgia – the lullaby of the late night shipping forecast that Juliet hears on her Philetta and that soothes her to sleep.

And most reassuring of all the closing of the Children’s Hour – broadcast at 5pm. The name is from the Longfellow poem

The Children’s Hour

Atkinson uses these rather creaky clichéd references to good effect. When she piles on the historical background she does so with a light touch.

Anna Wolkoff herself had pinned it. She had fierce eyebrows and seemed mournfully Russian sighing in the tragic way of a woman whose cherry orchard had been chopped down … ‘You are one of us.’

But let’s get back to the most important part of the book: Food.

Atkinson deftly uses the food to reveal the contrasting lives her characters and the flavor of the times. There are the limp sandwiches and frugal meals and then the gourmet dinners and extravagant excess of another. There’s rationing still in effect in 1950 and then there’s Elizabeth David blazing onto the scene with a tantalizing glimpse of a world of Mediterranean sunshine. While there’s not much evidence that Juliet liked to cook or that she knew anything much about the Mediterranean, Atkinson’s deft reference brings contrasting worlds into sharp relief. It’s a great period detail and the theme of food and drink – bad and worse versus luxury gourmet – runs through the novel.

And to give the food it’s proper place at the blog table I am leaving it to the next post. I’ve had a lot of fun tracking and tracing the meals. But do read the book if you haven’t done so already.

Thanks for drawing this book to my attention; I really enjoyed it. The author evokes a very credible period atmosphere.

I’ve just read ‘Agent Jack’ by Robert Hutton which is a non fiction account of the same MI5 operation. ‘Agent Jack’ was the real life ‘Gestapo agent’ who ended up running a network of 500 people who believed they were working as a fifth column for the Nazis. Fascinating stuff! -and confirms the authenticity of Kate Atkinson’s background research.

I just finished her “Big Sky” and didn’t think it was a patch on “Transcription” although she does have a terrific way of building in the details. The story races along although it’s hard to keep all the threads and characters straight. In the end it was all a bit too gruesome – dead bodies and coincidences abound. I will have to look for “Agent Jack”. Sounds interesting. Loved all the period stuff in “Transcription”. Atkinson is really good at that kind of stuff.