Yeats wrote the poem “The Wild Swans at Coole” (see Game of Swans) in 1916 /17 when he was staying with Lady Gregory at her home in Coole Park, Galway and feeling lovelorn.

And all he did done perfectly

As though he had but that one trade alone”

‘In Memory of Major Robert Gregory’ — W.B.Yeats

In 1919 he used the title for a collection of poems that he dedicated to her son – Major Robert Gregory – the Royal Flying Corps fighter pilot who plunged to his death in Italy in January 1918.

Two of the poems in the collection are about Gregory – the best known of which is An Irish Airman Foresees His Death. In the poem Yeats projects his own feelings about the war onto his Irish airman – Robert Gregory.

Before he died Gregory and Yeats were not always on friendly terms. His mother and Yeats were artistic collaborators and Lady Gregory was Yeats’ great patron, collaborator and literary companion in their work promoting the Irish Literary Revival.

Coole Park was an important meeting place for writers and artists. after the death of Lady Gregory’s husband. Yeats was a frequent visitor at Coole and Gregory resented that Yeats stayed in his father’s bedroom and he put restrictions on Yeats’ access to the wine cellar.

Lady Gregory wrote briefly to WB Yeats: ‘The long dreaded telegram has come – Robert has been killed in action ….it is very hard to bear.’

Gregory had volunteered for the Connaught Rangers 1915, transferring shortly afterwards to the Royal Flying Corps where he proved an excellent pilot.

In France he was stationed near Lens and flew patrols over the Somme and Ypres battlefields. In September 1916, he was shot down while escorting a bombing raid. His plane was destroyed, but he walked away unhurt.

In March 1917 his squadron was ambushed by Baron Von Richtofen’s Red Circus, and systematically butchered. Nine planes were shot down, four pilots were killed, five survived. Gregory was one of them. During that fight it is almost certain that Gregory fought one-to-one combat with the Red Baron, forcing him to fly away.

In November 1917 he was transferred to the Italian front.

Gregory was awarded the Military Cross ‘ …for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. On many occasion he has, at various altitudes, attacked and destroyed or driven down hostile machines, and has invariably displayed the highest courage and skill.’ The French awarded him membership of the Legion d’Honneur.

George Bernard Shaw met Gregory on a visit to the Western Front in February1917. He wrote to Lady Gregory after her son’s death:

When I met Robert at the flying station on the west front, in abominably cold weather, with frostbite on his face hardly healed, he told me that the six months he had been there had been the happiest of his life. An amazing thing to say considering his exceptionally fortunate and happy circumstances at home, but he evidently meant it. To a man of his power of standing up to danger – which must mean enjoying it – war must have intensified his life as nothing else could; he got a grip of it that he could not through art or love. I suppose that is what makes the soldier.’

Lady Gregory asked Yeats to write a memorial to her son in poetry. Yeats had been reluctant to write about the war but he wrote four poems about Gregory. She was unhappy with the first – ‘Shepard and Goatheard’ and was so distressed with the final one – ‘Reprisals’ – that it was not published until after both their deaths. For ‘Reprisals’, Yeats took his inspiration from Shaw’s letter. Lady Gregory lamented: “he quoted words which GBS told him and did not mean to repeat – and which will give pain – I hardly know why it gives me so extra-ordinary pain…I fear the night.’

Reprisals

Considering that before you died

You had brought down some nineteen planes,

I think you were satisfied,

And life at last seemed worth the pains.

‘I have had more happiness in one year

Than in all the other years,’ you said;

And battle joy may be so dear

A memory even to the dead

It chases common thought away.

Yet rise from your Italian tomb,

Flit to Kiltartan Cross and stay

Till certain second thought have come

Upon the cause you served, that we

Imagined such a fine affair:

Half drunk or whole-mad soldiery

Are murdering your tenants there;

Men that revere your father yet

Are shot at on the open plain;

Where can new-married women sit

To suckle children now? Armed men

May murder them in passing by

Nor parliament nor law take heed; –

Then stop your ears with dust and lie

Among the other cheated dead.

– W.B. Yeats (23 November 1920)

Gregory was buried in Padua and although the cemetery record states that he was killed in action, the circumstances are not certain. His death has usually been attributed to friendly fire – shot down in error by an Italian pilot. Engine failure was another possibility.

Another conjecture is that he lost consciousness at high altitude and lost control of the Sopwith Camel he was flying.

Another theory proposed recently is he was a victim of the influenza epidemic.

The Irish Times had the story:

…at last October’s “Autumn Gathering” in Coole Park, where admirers of Yeats and Lady Gregory (Robert’s mother) meet annually to discuss literary and related matters, the phantom Italian was for once and all exonerated from any blame.

Among the speakers at the 2017 event was Geoffrey O’Byrne White … who declared categorically that Robert had not been shot down, but that he instead just lost consciousness at the controls, probably as a reaction to a flu vaccination.

He had been inoculated on the morning of his flight,” O’Byrne White told the audience (as quoted by RTÉ). “He probably passed out at high altitude in an unstable aircraft. It was the inoculation that killed him, in my view.”

This would also have been in keeping with a letter Lady Gregory wrote to a friend in 1918, soon after hearing of her son’s death, in which she said he had been returning from enemy territory “when at a great height they believe he fainted and did not come back to consciousness in this world”.

There’s a couple of problems with this theory. The great ‘Spanish’ influenza outbreak of 1918-1919 did not really take off until several months after Gregory’s death. And, as there seems to have been no available vaccination at the time, it seems highly unlikely that Gregory was inoculated against influenza. If he did receive an inoculation that morning it was more likely to have been for enteric fevers (typhoid). Side effects – fever, headache, dizziness – were common.

So, the “Spanish” flu inoculation theory is improbable.

And of course there was nothing “Spanish’ about the deadly ‘flu pandemic of 1918-1919 that killed 50 million and upwards worldwide. Censorship in the combatant countries of WW1 kept bad news hidden. Information about the disease came from neutral Spain. And the association stuck.

In Spain – where the disease killed King Alonso X111 – they had their own names for the disease. They called it the “French” flu based on the theory it was carried my migrant workers passing traveling back and forth to France. It was also known as the “Naples Soldier”. This was the title of a popular song in an operetta La Canción del Olvido (“The Song of Forgetting”), that had a very successful run in Madrid at the time of the first major flu epidemic in Spain.

The librettist is said to have joked that Naples Soldier was “as catchy as the flu”.

The ‘flu has been around for ever it seems although the word influenza wasn’t used to describe a disease until 1357 when people called an epidemic in Florence, Italy influenza di freddo – “cold influence,” referring to their thinking about the disease’s possible cause.

That deadly 1918-1919 pandemic provides something I have in common with Donald Trump. Both of us have grandfathers who died of the ‘flu. In May 1918 Friedrich Trump – an immigrant from Bavaria – was walking with his son Fred when he suddenly felt very ill and was rushed to bed. The next day he was dead. He was 49 years old.

That epidemic gave rise to the children’s skipping song – yet more proof of the callous, beastly, heartless resilience of children.

“I had a little bird

His name was Enza

I opened the window

And in-flew-Enza.”

I got my ‘flu shot yesterday. How about you?

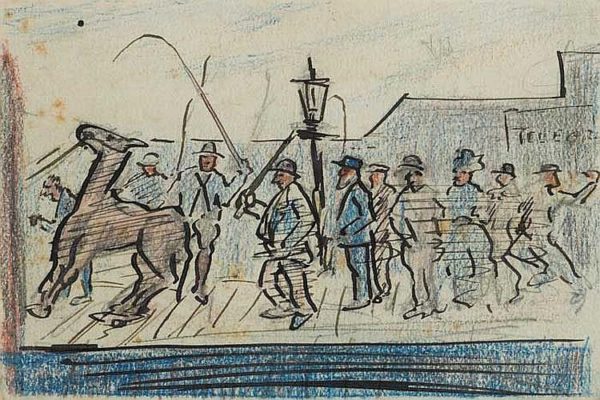

The Trail of War

Sydney William Carline (1888–1929)