The Year Begins in October

Armistead Maupin based his vignettes of gay life in 1970s San Francisco – Tales of the City – on Jan Struther’s Mrs. Miniver (1939). They first appeared in a long-running serial in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Instinctively I wanted to write a gay male Mrs Miniver, the minutiae of gay life with Michael Tolliver as the observer. – Armistead Maupin

And surely Jan Struther had Mrs. Dalloway (1925) in mind.

Mrs. Miniver bought the flowers herself.

It was lovely, she thought, nodding good-bye to the flower-woman and carrying her big sheaf of chrysanthemums down the street with a kind of ceremonious joy, as though it were a cornucopia; it was lovely, this settling down again, this tidying away of the summer into its box, this taking up of the thread of one’s life where the holidays (irrelevant interlude) had made one drop it.

I’ve had this second-hand paperback copy of Mrs. Miniver sitting on my shelf for at least 25 years. I thought it was time to read it.

I’ve had this second-hand paperback copy of Mrs. Miniver sitting on my shelf for at least 25 years. I thought it was time to read it.

And so I did.

Mrs. Miniver is a series of light-hearted vignettes – observations and musings about upper-middle-class family and social life in the late 1930s. They were originally published on London Times Court page opposite news about the royal family.

They were an instant hit with readers and a bestseller in the UK and USA when published in book form. And then, of course, Mrs. Miniver took on a new life and became immortal (as it were) in the sickly sentimental William Wyler film of 1942 starring Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon.

By the time the film came out, American was at war but while he was making it Wyler was concerned about American isolationism. It was effective propaganda that helped galvanize American audience support for the war.

Mrs. Miniver lives in a stucco-fronted house on a leafy square in Chelsea

Stepping lightly and quickly down the square, Mrs. Miniver suddenly understood why she was enjoying the forties so much better than she had enjoyed the thirties: it was the difference between August and October, between the heaviness of late summer and the sparkle of early autumn, between the ending of an old phase and the beginning of a fresh one.

At home, upstairs in the drawing-room:

She unwrapped the chrysanthemums and arranged them in a square glass jar, between herself and the light, so that the sun shone through them. They were the big mop-headed kind, burgundy-coloured, with curled petals; their beauty was noble, architectural; and as for their scent, she thought as she buried her nose in the nearest of them, it was a pure distillation of her mood, a quintessence of all that she found gay and intoxicating and astringent about the weather, the circumstances, her own age and the season of the year.

Life is Good

On her writing-table are the invitations to the parties and events of the season. Her son at Eton has written with a request to send his umbrella, his camera, and his fountain pen, which leaked rather. But that does not spoil Mrs. Miniver’s mood. There’s a bright fire of logs and warmth from the sunshine. The tea is laid with honey sandwiches and brandysnaps and there are new library books on the fender stool. The mantelpiece clock chimes and a tug hoots on the river. There’s a whiff of a bonfire in the air and a familiar barrel organ playing “The Blue Danube” from the other end of the square. Life is good and all’s well with the world.

October suits Mrs. Miniver best. For her, it was always the first, the real New Year. That laborious affair in January is nothing but a name. She bought the flowers herself for the pleasure of it. But there are servants to bring up the tea when she rings her bell.

Struther’s book concerns itself with the daily life of Mrs.Miniver, her successful architect husband, and three children. There are visits to Starlings – their house in Kent, to the duck-pond in Hampstead Heath, the seasonal routines of Guy Fawkes night, Christmas shopping, and holidays in Scotland. She shops for a new diary and muses on the pleasures of sharing commentary on the day with her husband. She takes pleasure in simple things and her wry observations on domestic doings and the lives of her family, neighbors, servants, and friends make this a lively, light-hearted read.

But this is the late 1930s and war is on the way. Mrs.Miniver takes her children to have them fitted for gas masks and feels grateful that this time the war would be not against a people but an ideology:

If the worst came to the worst (it was funny how one still shied away from saying, “If there’s a war,” and fell back on euphemisms) — if the worst came to the worst, these children would at least know that we were fighting against an idea, and not against a nation. Whereas the last generation had been told to run and play in the garden, had been shut out from the grown-ups’ worried conclaves: and then quite suddenly had all been plunged into an orgy of licensed lunacy, of boycotting Grimm and Struwwelpeter, of looking askance at their cousins’ old Fräulein, and of feeling towards Dachshund puppies the uneasy tenderness of a devout churchwoman dandling her daughter’s love-child. But this time those lunacies — or rather, the outlook which bred them — must not be allowed to come into being. To guard against that was the most important of all the forms of war work which she and other women would have to do: there are no tangible gas masks to defend us in war-time against its slow, yellow, drifting corruption of the mind.

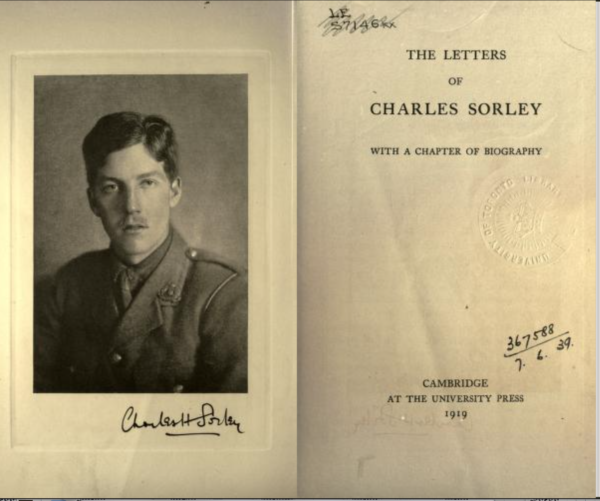

Lines like that remind me of the comments the poet Charles Sorley made in his letters. In July 1914, Charles Sorley was in Germany on a walking tour following a half a year living with a German family and studying at the university in Jena.

When war was declared he was arrested and held overnight. He was released and made his way back to England. The day after his arrival home Sorley applied for a commission in the army. When he did not hear back he considered enlisting as a private but before that happened he heard that he had been gazetted as 2nd lieutenant in the Suffolk Regiment and was soon training on the Berkshire downs at Churn.

In a letter to his sister he wrote:

It’s a beastly nuisance this war, especially as it’s against such nice people as the Germans.

By then of course anti-German sentiment was raging in Britain. As Mrs. Miniver observed, WW2 was to be a little different.

As for Charles, now Captain, Sorley – who had many German friends – he was shot through the head by a sniper at the Battle of Loos on October 13th, 1915. Together with over 20,000 officers – who have no known grave and were killed in the area – Sorley is commemorated at the Loos Memorial at Dud Corner Cemetery.

Eighteen years later, in London, the fictional Mrs. Miniver reflects on the passing of the year:

As she turned away from the window the date on her writing-table calendar caught her eye. Just a year ago, she remembered, she had stood at that same window putting the summer away and preparing to enjoy the autumn. And here she was again: only this time it wasn’t chrysanthemums she was rearranging, but values.

And among those values are her feelings about her material possessions, what matters most and what binds people in common humanity:

How could there be this ridiculous talk of war, when little boys in all countries collected stones, dodged cleaning their teeth, and hated cauliflower?

Indeed, what always struck her when she went abroad was how much stronger the links are between people of the same calling than between people of the same race: especially if it is a calling which has more truck with the laws of nature than with the laws of man. The children of the world are one nation; the very old, another; the blind, a third: (for childhood, age and blindness are all callings, and hard ones at that). A man who works with wood, a man who works with iron, a man who works with test-tubes, is more akin to a joiner, a smith, a research chemist from the other end of the earth than to a clerk or a shopkeeper in his own town.

And, sipping her black coffee, Mrs.Miniver imagines a solution: If governments spent money on bringing people together for free holidays – a certain number for each district – instead of buying bombers …

I wrote earlier that I find Wyler’s film version gooey and sentimental. And it is. But there is no doubt of his serious intentions. And there is no doubt about its impact. Wyler was well aware of the dangers of fascism and he was alarmed by the outbreak of the war. Concerned about profits and the European market, Hollywood took a determinedly neutral attitude. Wyler wanted to change attitudes and he succeeded. Given the current state of affairs, we could do with such effective defenders of democracy right about now.

Here’s the trailer for the film version:

This sounds delightful! I suppose I vaguely knew the movie was based on something but I knew nothing more and I have never seen more than the opening credits. I like books about the ordinary things people did during wars.

It’s funny, though, I just read a Joanna Trollope in which one character is a very prosperous architect. As a lawyer who used to do construction law, I encountered many architects who were not doing very well and had a hard time paying off their student loans. Maybe it was just easier to get by financially in the past.

Constance´s last blog post ..A Flicker in the Dark by Stacy Willingham

It is a delightful light read. And wonderfully well written. My experience with architects has been much the same.

Jan Struther – the author Joyce Anstruther Maxtone-Green – came from wealth and was actually married to a Lloyd’s stockbroker who was Scottish landed gentry.

I remember loving the movie but I must have been a child when I saw it. It would be worth a second look.

Not mooch on the film of Mrs Miniver, but Struther’s writing as quoted here is seriously good. And I never knew.

It’s surprisingly good. Stephen Vincent Benet said that the sketches were “beautifully written, with form, with style and a deceptive simplicity . . . every word is in place, like the flowers in a beautifully tended garden. Mrs. Miniver also manages to project the warmth and wisdom of an engaging personality.”

They certainly charmed readers on both sides of the Atlantic.

When I was oh so young, I loved Mrs Miniver and The Miniver Story….so many tears. It didn’t seem corny then!

It’s a good sentimental weepy. And was oh so effective.

The book made Jan Struther into a Book-of-the-Month celebrity in the US.

The film changed popular attitudes.

The book is quite different and has none of the Dunkirk, Blitz, belligerent German pilot stuff.

And the real Jan Struther did not like tea!

I just love those old trailers!

All those comic working-class folks cheerfully upholding British Values and the Empire.

Jolly japes interspersed with stiff upper lips.

As the last scene of the film declares: “This is the People’s War. It is our war.”

Thank the Lord for the Beveridge Report and the sanity of the 1945 electorate.

They must be turning in their graves now!

Absolutely. The great British betrayal by Boris and Brexit. Tragic stupidity.