All our stories begin before we are born. Not Just the blue eyes or flat feet we inherit, but the stories we hear from uncles and aunts, from grandmothers and grandfathers. Even if oral history is no more reliable than the party game of Chinese whispers, everyone bringing to it their own subjective lumber of myths, half-truths, fancies and deceits, it is still these family stories that tell us who we are and help to shape our lives. – Nina Bawden, In My Own Time

Reading biographies I often wonder how it is that other people always seem to have such interesting stories to tell. Other people’s families seem stuffed with eccentric relatives, family secrets, and skeletons in the wardrobes and under the stairs and everywhere.

Reading biographies I often wonder how it is that other people always seem to have such interesting stories to tell. Other people’s families seem stuffed with eccentric relatives, family secrets, and skeletons in the wardrobes and under the stairs and everywhere.

But then – that is the art of a good storyteller: the capacity to transform the quotidian into something that has magic, drama, and interest. Nina Bawden was just such a storyteller. And is that gift that makes her own story – In My Own Time: Almost an Autobiography – such a delight to read.

There’s her grandmother Emily Edith who once faced off a shot-gun waving suitor at the Harvest Fair and who was proud to tell the story of her mother who once emptied a pail of afterbirth on a doctor’s head.

We don’t stand for that family

Edith Emily manages to be anarchic, respectable, and undeferential. At the cinema:

We were usually there when ‘God Save The King’ was played at the end of the evening, and my grandmother always insisted we stay in our seats while the rest of the audience rose obediently. ‘We don’t stand for that family,’ was all she would say in explanation, although one of my aunts later suggested that it might have something to do with an incident on a road near Sandringham when a minor royal had driven past my grandfather and splashed mud on his only suit.

The Gamey Stew of Family

Bawden’s comment..

There are more ingredients in the gamey stew of family life than can be easily counted: the best anyone can do is to sniff and taste – and ask the right questions at the right time. The pity is that by the time the questions are clear, those who know the answers are usually dead.

…reminds me of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala – the writer, and screenwriter of the Merchant/ Ivory films. She was a keen observer of people and claimed that she could gather a year’s worth of writing material by attending just one dinner party.

Carrie’s War, A Modern Classic

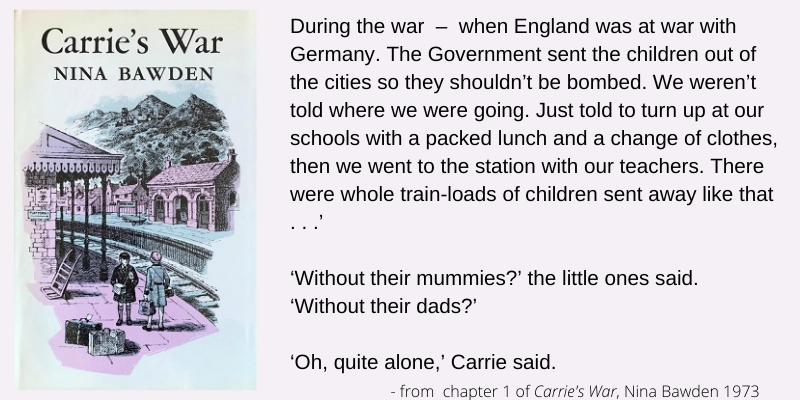

Nina Bawden was a prolific author of novels for adults and children but Carrie’s War (1973) – is probably her best known. It’s the story of two middle-class children – Carrie and her brother Nick – who are evacuated to a mining town in South Wales, and about the ways in which their lives become entangled with the people they meet.

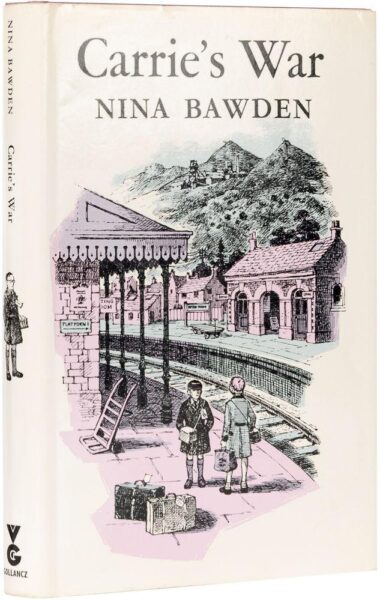

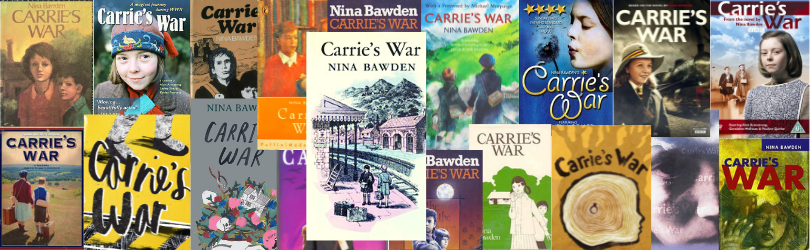

Carrie’s War now has the status of a modern classic. It’s been televised and dramatized and is a staple of the school stock cupboard and worksheet. Looking at all the covers and posters from the various editions and versions I wonder if some of those illustrators actually read the book.

Carrie’s War now has the status of a modern classic. It’s been televised and dramatized and is a staple of the school stock cupboard and worksheet. Looking at all the covers and posters from the various editions and versions I wonder if some of those illustrators actually read the book.

My favorite cover remains the first edition by Faith Jaques. Her illustration shows its two children facing each other on a deserted railway platform. They have their gasmasks and school uniforms and their small cases are close by. There’s a empty porter’s trolley, a sign for the waiting room, and the platform canopy has fretted daggerboard fascia. In the distance, there are coal tips and a pit head The single track bends away along the valley.

Jaques captures the emotional tone of the novel – the sense of bewildered abandonment and uncertainty of the children, and the feel of the place and time. Her illustrations throughout complement Bawden’s story.

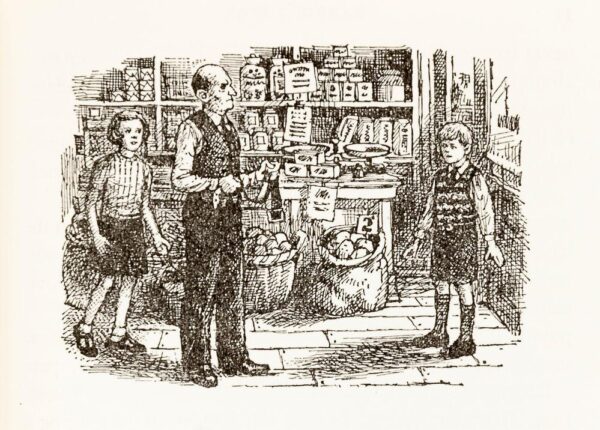

Here is the scene where Nick is caught helping himself to a biscuit in the shop with Mr. Evans taking off his belt and Carrie trying to mediate the crisis.

Nina Bawden was herself a wartime evacuee – first to Ipswich and then to South Wales. That experience informs her novel.

Except in the coded way that most novelists make use of their lives, cannibalising rough odds and ends of experience to make a tidy whole, Carrie’s War is not my story. But Blaengarw was the town where some of us had been billeted for a week when our school was moved from Suffolk to Wales. It was our first sight of a mining valley; the black pit-head machinery, the smooth cones of the slag heaps dark against the sheep-cropped green mountains, the narrow streets of terraced houses steeply climbing from the central main street like bristles from a spine.

A little older than Carrie, Nina is ready for adventure when she was evacuated with Ilford County High School.

We were a lucky generation. A lot of our teachers were the childless spinsters of the First World War; women in their forties and fifties whose unused, creative fire had been channelled into teaching little girls. Among these excellent women was an English teacher who was able to communicate the glorious excitement she still felt herself when she read a poem or a play, a Latin teacher who could make me understand that the prose style of Tacitus was a wonder of rhythm and economy, and Miss Clark, a History mistress who was a member of the Fabian Society and determined that as well as understanding the Chartist movement and the Congress of Vienna, the girls she taught should be alive to what was going on around them.

Chamberlain came back from Munich, waving a silly piece of paper. Miss Clark talked about appeasement, and her face was grave… Like her, I was disappointed that there was to be no war, but for different reasons. I was restless. I had recently begun to feel tamed and constricted…. I felt I understood my mother’s boredom with our dull suburban life. Even if she hadn’t pointed out to me that it was dull, I think I would have known by now that the grass was greener elsewhere; that there was a better life, where people lived in beautiful houses and had interesting conversations and adventures. (I had read about this life in books; reading, which is supposed to enlarge the mind was, by this time, increasing my discontent.)

Nina is ready to leave home. She writes a tear-jerking piece about the sadness of a wartime child torn from her loving family which was published in the local newspaper, the Ilford Recorder. Her true feelings were quite other.

Plans to evacuate children from the cities filled me with anticipation. I didn’t want to leave home, or at least, I said I didn’t to my mother, but in fact, deep down, the prospect thrilled me. A dazzling future beckoned. I saw myself living in a big house in the country with rich and educated and even titled people who drove about in beautiful old cars, always ate with candles on the table, fell in and out of love with each other, and generally had a wonderfully exciting life like the people in the Dornford Yates novels I had just become addicted to.

As part of Operation Pied Piper, Bawden and her classmates and teachers were evacuated a few days before war was declared.

We were allowed to take two things with us, a small suitcase, light enough to carry, and a gas mask. We were given luggage labels with our names and addresses written on them to thread through our blazer buttonhole. I angered a normally indulgent teacher with what seemed to me a perfectly sensible complaint. ‘It’s silly for me to wear a label. I’m not luggage, and I’m not a baby. I should have thought I was quite old enough to know where I live and who I am!’

Bawden outlines the years she spent as an evacuee – seven different billets with seven different families. After a short time in Ipswich (deemed too likely to be in the invasion zone) the school moved to South Wales. Nina’s carriage is separated from the train and for a short while she stays with a mining family in Blaengarw which the BBC later chose as the location for their TV serialization of the novel.

It was our first sight of a mining valley; the black pit-head machinery, the smooth cones of the slag heaps dark against the sheep-cropped green mountains, the narrow streets of terraced houses steeply climbing from the central main street like bristles from a spine.

And for most of us it was our first real encounter with social injustice. The mines in Blaengarw had been closed in the 1930s because there was no profit in them; they were old, deep mines, dangerous to work without new and expensive machines and safety equipment. There was no other work for the miners; only a bit of light industry at a bigger town down the railway line for their wives and their daughters. The week we arrived, in the spring of 1940, the money for the necessary improvements had suddenly been found, the pits had been opened, and the town was en fete. It was as if we had tumbled into a festival, a carnival, an explosion of joy. There was no feeling in Blaengarw that week that we were at the beginning of a long, draining war. To this valley, the war meant work at last; life and dignity.

Nina is with her school friend Jean and they are happy there,

We walked on the mountain, drank cold, sweet water from a spring, and went home to a kitchen that smelled of baking bread… I wished I could have stayed with this happy family for ever and at the end of that short week I cried when I left them, as I hadn’t cried leaving my mother and brothers in London. But most of the girls in my school had been sent to Aberdare, the town that is called the Queen of the Valleys, where there were both enough billets and a big grammar school building which we were to share. That some of us had been sent to Blaengarw instead had been an administrative mistake.

What follows is a series of billets and a lot of growing up. There are the odd behaviors of other people’s families, the unwanted amorous advances (we might call that something different these days), and some of the host families are sketchy to say the least.

In her fifth billet, she stays with Mr. and Mrs. Jones

Mrs Jones, was a sad, nervous woman, hopeless at just about everything. She cleaned the floors; that is, I know she tried to clean the floors because I saw her on her hands and knees on the stone flags of the kitchen with a bucket of water and a scrubbing brush, but huge, glossy black beetles scuttled into the corners if you opened a cupboard. She shrank woollen clothes when she washed them – and she refused to let us wash our own things because she said it would make her ‘look stupid’ in front of the neighbours. Her idea of a festive meal was tinned pilchards, heated until lukewarm in the oven and served straight from the tin, and her conversation was limited to gruesome descriptions of the liver disease that had killed her only daughter, and her own operation for cancer. Her stomach was like a pincushion from the radium needles, she said.

When Nina’s mother comes to visit she is anxious to protect Mrs.Jones from her mother’s contempt for her inadequacies. She sings Mrs. Jones praises and does not tell her of the nighttime behaviors of Mr. Jones.

I didn’t tell my mother that there were nights when our foster father would walk round the house in his nightshirt, carrying a guttering candle, and stand for some dme, silently, beside the bed where we lay, eyes closed, feigning sleep. (‘Mr Jones sometimes goes mad at the turn of the moon,’ Mrs Jones had explained, early on. ‘All his family are the same way. His brother hanged himself behind the kitchen door when the moon was full; he was big and heavy and it took several men to push the door open. But there’s no need to worry about Mr Jones, he has his funny habits at that time of the month, so you just take no notice.’)

Typically, accounts of wartime evacuation concentrate on the shock of middle-class families who receive slum children ridden with lice and no table manners. Evelyn Waugh provides an extreme and dyspeptic example of this in Put Out More Flags.

For Nina and the girls of Ilford County High School, it was quite the reverse. Because of the selective educational process of dividing the sheep from the goats at age 11, most of them were from what her mother would have called respectable homes, and some of them quite prosperous. This meant that many were billeted in homes much poorer than their own.

One girl was so shocked by finding that the only lavatory was at the bottom of a cottage garden that she went back to London at the end of the first week.

Nina is unphased by the outdoor toilets but she finds the lack of books strange.

For her, her years in South Wales were a radicalizing experience. She learns about class and class differences and sees the exploitation of the miners. She hears Aneurin Bevan speak and reads The Ragged Trousered Philanthropist.

And always the emotional complexity. For Mr. and Mrs. Jones she develops a fierce and protective loyalty while at the same time making fun of their strange ways to classmates and in letters home. When she finds her mother has taken her seriously and she is prevented from returning to them after a summer holiday she is guilt-ridden at her betrayal.

As the war winds down Nina returns to London thrilled to be able to experience the time of the doodlebugs. She wins a scholarship to Oxford where she is a classmate of Margaret Thatcher and has a date with Richard Burton. In 1945 she campaigns for the Labour Party and for Ian Mikardo in his reading constituency.

The years in South Wales were just a small portion of a long and busy life but they had an enduring influence. In My Own Words is a most readable account of that life. The war and the experience of being evacuated were crucial.

Everyone in my generation was affected by it. It’s the most important thing I can remember from being young. It happened during the most formative part of my childhood – from 14 until I was 21… it had gone on for so long, it was just part of one’s life.

This is how she sums it up:

In August 1939, leaving London on the train to Ipswich, I had been alight with excited anticipation and I had not been disappointed. Life in other people’s homes was always interesting if not always comfortable; you might have to eat Mrs Jones’s food, but Mr Jones (a sweet man in his wits) was an adventure.

I am fascinated by evacuation stories and am surprised I have never read Carrie’s War. I just read A Place to Hang the Moon which was charming but more suited to a 10 year old.

I don’t know that one. Will have to look it up. Thanks.

Excuse me for skimming and skipping large parts of this: I’m part-way through Bawden’s memoir, paused while I read another of her children’s novels but not picked up again. I’ll come back here when I’ve got through it. Carrie’s War was the first of hers I read, and it’s been followed by three others.

I will seek it out.

This is fascinating. I know Nina Bawden’s name but have never read her. What an interesting and feisty woman.

She truly was. And deeply humane and decent.

The rest of her story is equally as fascinating and as full of ordinary and extraordinary stuff of life. And throughout all her triumphs, trials, and tribulations – a son whose body was dragged from the Thames, a husband who was killed in a train crash that left her grievously wounded – she never lost her sense of perspective nor her humanity and capacity to care.

“Carrie’s War” is the book I know her for. I actually “taught it for a few years on London in the 1970s and know little bits of it by heart from my reading aloud in my “Welsh” accent. I can see how it was informed by her own experiences.

Now it’s time to read her other work for children and for adults. “In My Own Words” is a delightful read

After my parents were gone, the questions arrived, so many of them. Why does that happen? So many were such obvious things to ask. My Dad was in Malta during the siege. Then he was evacuated home via South Africa in a hospital ship, but although he spoke of South Africa, he never talked about the long, dangerous trip north. We don’t know the nature of his illness. I was always told he had one lung, presumably after surviving Spanish ‘flu in 1917. But I was responsible for him as an old man. He had two lungs, certainly. Why such a story? My brother was told never to ask about the war, (I was not) so did he have a mental break down? Mum was in London for the duration, running a boarding house. I think as a result she became immune to drama. No situation was ever worth making a fuss about. I grew up minimizing things that I should have made a big fuss about, but it wasn’t our way. I was born in ’48 but that war still lives with me.

With you on all of that.

So many stories and half-stories and secrets. I think that many of us from our generation lived in the shadow of that war (and the one that came before) that loomed so large in our parents’ lives. Just look at the outline you have created here. It is the stuff of novels and drama. And it was the ordinary world of the ordinary people with whom we grew up.

Do you think it matters to try and recreate and reimagine or at least record the stories we were told? I do.