Good friends, gone now.

Good friends, gone now.

Their photographs on my wall.

Until some stranger takes them down, throws them away.

No reason to keep them after all.

Last week I learned via a Facebook post that Marty Sternstein had died on April 18th. This past week has seen a a social media outpouring of tributes in his memory.

Marty was 78 when he retired in 2010. He touched the lives of hundreds of students and colleagues who remember him with love, respect and gratitude.

Juliana May wrote of Marty’s enduring impact on her life:

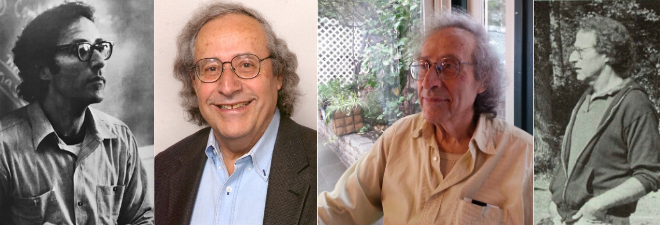

And she chose the perfect photograph to accompany her words.

There can be no gathering or memorial service at least not for now. As word spread on social media it became the gathering place for collective grieving and sense of loss. The anecdotes, memories and tributes from his former students poured in.

They remembered his kindness, his blue sweatshirt and khakis, the ice clinking in his capped container of iced coffee, his gap-toothed smile, his love of Bob Dylan. They wrote of his influence on their life choices, love of literature, use of commas. They called him wise friend, mentor, philosopher, guide and – most of all – great teacher.

On Twitter and Instagram David Netto wrote:

And he included this remarkable photograph:

Marty taught English first at a public school in New Jersey and then at the Walden School in NYC. And – when that school merged with New Lincoln in 1988 – at Walden Lincoln.

Here’s a photo of Walden faculty and staff from the1987 yearbook. Marty is there along with Miriam Colon. Lois Hilton, Cecille Little, Bob Roseen and Sue Sortino all of whom also became a part of The Day School in 1991.

When the then Day School acquired the assets of Walden Lincoln in 1991 Marty became one of the founding figures of the high school of what is now Trevor Day School. When he retired he did not want any any kind of event or celebration to mark the occasion.

A month ago Zack Garlitos wrote:

I had an English teacher in high school, Mr. Sternstein, who told us an anecdote one of the first days of class. A teacher brings a goldfish to class one day, and tells their students to write down every observation they can make about the fish. The next day, the teacher has the same fish, and gives the same assignment. The students, however, are not allowed to make any of the same observations they made the day before. “But we already recorded all of our observations yesterday,” the students say. “Do it again,” the teacher tells them. So they do, and they each make a list of new observations. The next day, the teacher brings the same fish, gives the same assignment. The students make a new list. This goes on for days, and each day the students realize there is always something new to notice about the fish. We would come back to this anecdote from time to time throughout the school year. When someone would find themself stumped, Mr. Sternstein would remind us, “Look at the fish.” I returned home from the Philippines on March 15, 2020 with a mild cough. I’ve isolated myself in my apartment for the past week-and-a-half; the only meaningful human contact I’ve had has been virtual. I’ve been battling the pressure I feel to document this bizarre moment in human history from the confines of my room, the existential dread of not knowing what lies at the end of this tunnel, the fear and loneliness that I associate with isolation. I find myself longing to make photographs that are not explicitly about our collective circumstances, because I feel that in some way, whatever I create right now will, inevitably, be about this moment. The fish changes: sometimes it’s the fading tulips on my kitchen table, other times it’s the detail in the parquet floors, others the way the steam rises from my cup of coffee, and—perhaps most frequently—my own life, patterns, and choices. Amidst the fear and uncertainty, I am grateful to have a moment to slow down, to process the trip from which I just returned, to consider my surroundings and relationships and be thankful for them. – https://imgund.com/zackgarlitos

There’s a video somewhere of Marty teaching a class of I think ninth graders. He is leading a discussion of Great Expectations. And what I remember is how Marty was eliciting from the class just how their own experience of life and relationships connected with Dickens’ characters.

Pip and Estella were not some alien figures in an old book that was supposed to be good for them to read – but adolescents with feelings and emotional lives, just like theirs. Marty had that indwelling quality. The literature he loved was a part of who he was and the fabric of his life. It is that that he shared with those students. They too could look closely. And find connection and meaning. And look again at the fish.

I could not find any official obituary or death notice on line but I did find a note from a funeral home saying that Marty would be buried at Mount Hebron Cemetery in Flushing. That is where his parents Samuel and Pauline Sternstein are buried.

Marty was a writer. And this week I found something of his that was published in the Birmingham Review in 2016. I believe it to be autobiographical based on what I know of Marty’s parents and childhood.

Marty was born in 1932 and when he was seven he was living at 2551 Aqueduct Avenue in the Bronx,

Marty was born in 1932 and when he was seven he was living at 2551 Aqueduct Avenue in the Bronx,

His father was fifteen when in 1911- as Schulem Sternstein – he left Uman, Russia and arrived in NY via Liverpool on the RMS Caronia.

Marty writes of his father owning a diner and commuting daily by subway to Brooklyn. At the time of the 1940 census he was listed as working as a waiter and had worked 72 hours the previous week.

His mother was born in Buczacz, Poland. She arrived in 1921 as Peppi Hoffman via Antwep on the SS Lapland. She was 22.

Buczacz was the site of multiple Soviet and Nazi atrocities both before and during WW2. Marty makes reference to his mother’ good fortune in emigrating and to her sister who did not. And there’s another – oh so understated – hint later of what became of her.

Between about 1890 and America‘s entrance into WWI in 1917, some 13 million immigrants arrived to make new lives in America. Most passed through Ellis Island, many settled in New York City. Seventy-five percent of them were Jews from Russia and Eastern Europe. Marty’s parents were part of that extraordinary wave of immigrants from Europe.

Marty was an only child. But there was another baby, an older brother.

A man is in his room looking at family photographs and he remembers. The complex contradictions of family deeply felt and gently remembered. It seems perfect for this moment

It is a remarkable piece of writing.

It is a remarkable piece of writing.

I take a deep breath and think of Marty.

Photos: @seventiesup (Facebook) Walden School Yearbooks, Trevor Day School.

This was a jolt, despite the fact it happened several years ago. Marty was my cousin. His mom, my Aunt Peppi, and my grandmother were sisters and best friends. They lived across the hall from each other in the same Bronx apartment building. Marty took the subway from the Village often to visit his folks and my grandparents. And also when we had the whole mishpucheh over for dinner on Passover or Rosh Hashanah.

My mom (5 years older than Marty) was close with all her cousins during my childhood. Marty made several trips on the LIRR to visit us when we moved to the South Shore. We ourselves were a small family (I’m an only child), but we were a big, loving, extended family. I grew up, went away to college, started my career in journalism. Then things changed. Neither my folks nor I know exactly why.

After my grandparents, Aunt Peppi and Uncle Sam died, I and my folks tried to stay close. Marty and my dad were of a kind and they always had friendly philosophical and political discussions. But now our phone calls weren’t being returned. My grandmother was the last of that generation to pass on, and it was if, somehow, a door had closed for my cousin.

My journalism career took me to many cities. Then I got the chance to go home again as an anchor and correspondent for CNN Financial News in NYC. One of the first things I did when I moved into my UWS apartment was look in the Manhattan white pages. There was Marty, still on Christopher St. I called, got the message machine, and left a long message telling my cuz I’m back and I can’t wait to get together again. No callback. I tried again a few months later. Same. It hurt. I loved my cousin and I know he loved me. Mom and I tried to figure out a reason, but we only came up with one… and, of course, could never get it confirmed.

I wasn’t back home for very long. Got laid off when Time Warner purchased Turner Broadcasting. But I managed to reconnect with many kinfolk I hadn’t seen in ages (including a mutual cousin Marty also lost touch with). With one glaring exception.

For years I searched online for any news that Martin retired or had any other life changes. Nothing. Mom died in 2016. Then I started looking for an obit, hoping I wouldn’t find one, but knowing that he was likely the last of the cousin group still with us and his time would come eventually.

Tonight was the first time I saw that dreaded obit (within this blog post). I’ll be honest… it hurts. Even though we were out of each other’s lives for decades, it still hurts a whole bunch. I can only hope he went peacefully and with a loved one to see him off. My love for my cousin never diminished despite what went down. He touched so many lives, as his extended family always knew he would. This has been cathartic for me to write, so thank you for the opportunity. And thanks to all of you who wrote so fondly of a wonderful guy.

I still miss Marty.

I don’t miss much else about my youth. But I do miss Marty.

He gave so many, so many gifts of attention.

He took kids yearning to learn seriously. What a gift!

I just wish I had taken the time to say Thank-You to him before this happened.

Thank-you Marty.

I will never forget you.

Marty was the teacher who changed my life. He was the man who showed me that literature was about life, my life. And that I had choices and choices mattered.

Thanks Lucas.

My heart still aches for Marty

Hello Jon – I think you are not alone. Marty was dear to so many. Thank you for adding your comment – another tribute to his enduring impact.

I came across this while explaining to my wife and kids what high school was like for me. Marty’s warmth, compassion and brilliance remain the anchor of my entire high school experience. Even now, 30 years after graduating, his guidance and counsel resonate with me almost daily.

Marty had a profound impact on so many over the years.

It was good to see your name pop up Adam.

Did you see this? https://www.josieholford.com/a-bit-of-history/

Oh my this makes me so sad. Marty was such a beautiful spirit—taught me to love NYC and writing in one and the same breath, literature, long walks, iced coffee and criticism. I tried to reach him unsuccessfully recently and am so so sad I didn’t have the chance to explore NYC with him one more time. I will still see him every time I step foot in the West Village.

Your comment captures Marty so well. Thank you. And so good to see you name pop up. Hope you are doing well. All best to you.

Marty was my teacher. I will never forget him.

I think there are so many who feel that way Jon.

So much to examine and return to examine in Marty Sternstein’s piece. Thank you for this ultimate tribute to a being who reminded those around him to enjoy the process.

Thank you.

Thank you for posting this, it’s a really nice tribute

I appreciate the comment. Thanks.

I love the impact one teacher can have on so many. When my English teacher died years ago, all the tributes were from students who had him in the few years he tolerated public high school teaching.

Marty had an impact on so many. And he was a wonderful colleague too. All students deserve to have Martys in their lives.

I never knew him until I read yr blog this morning. Waking up bored facing yet another day of lockdown his goldfish lesson inspired me to look at my life and surroundings each day with a fresh and enquiring mind. It is helping. Thanks Marty and thanks Josie x

Here’s the story of the “look at the fish”.

It’s about the test that Louis Agassiz, the nineteenth-century Harvard naturalist, gave every new student.

This is from a David McCullough interview in the Paris Review:

Agassiz, would take an odorous old fish out of a jar, set it in a tin pan in front of the student and say, Look at your fish. Then Agassiz would leave. When he came back, he would ask the student what he’d seen. Not very much, they would most often say, and Agassiz would say it again: Look at your fish. This could go on for days. The student would be encouraged to draw the fish but could use no tools for the examination, just hands and eyes.

Samuel Scudder, who later became a famous entomologist and expert on grasshoppers, left us the best account of the “ordeal with the fish.”

After several days, he still could not see whatever it was Agassiz wanted him to see. But, he said, I see how little I saw before. Then Scudder had a brainstorm and he announced it to Agassiz the next morning: Paired organs, the same on both sides. Of course! Of course! Agassiz said, very pleased. So Scudder naturally asked what he should do next, and Agassiz said, Look at your fish.

He made a difference in the lives of generations of students. And he was a wonderful colleague.

A beautiful tribute. He sounds like a truly remarkable man.