There’s a really useful article in Education Week that reviews, summarizes and connects the basic thinking and research out there on what helps promote creativity and helps children incubate the curiosity that leads to innovation, discovery and invention.

There’s a really useful article in Education Week that reviews, summarizes and connects the basic thinking and research out there on what helps promote creativity and helps children incubate the curiosity that leads to innovation, discovery and invention.

There’s little here that is new and indeed I have written on all of these topics many times but it is encouraging to see the chorus of voices swell. At Poughkeepsie Day School we have always been listening.

The first key point in that creativity and ingenuity – not test scores- are the competitive edge in a global economy. Education is about preparation for life not the workforce but is is mighty encouraging to know that the values, habits and skills we teach are the ones reckoned to help students earn a living.

But how is creativity to be taught? That’s the hot topic in education chatter from  the National Academy of Education’s annual meeting in Washington to the Learning and the Brain conference in Boston. As researchers start to get their measuring tools around that one, it is clear that that test-driven agendas can only serve to smother creativity.

the National Academy of Education’s annual meeting in Washington to the Learning and the Brain conference in Boston. As researchers start to get their measuring tools around that one, it is clear that that test-driven agendas can only serve to smother creativity.

I was delighted to see Shirley Brice Heath included in the usual round of suspects. Her ethnographic research reported in Ways with Words and What No Bedtime Story Means: Narrative Skills at Home and School made a big impact on me after their publication in 1983.

She compared two working class communities – Tracton and Roadville – with a middle class community and uncovered wide differences in literate traditions and modes of communication. Children from the mainstream middle class community were prepared for a more seamless beginning to the literacy modes of school. Heath concluded that successful teaching and learning depend on the elimination of boundaries between school and community. Early literacy teachers, for example, can only be truly effective when armed with understanding of the community’s attitudes toward reading and the complex factors that get in the way of understanding reading as an activity at the heart of the learning

She is now able to draw on that 30-year longitudinal research in new ways.

Now an English professor emerita at Stanford University, Heath told members of National Academy of Education at its annual research meeting that highlighted creativity and innovation: “To study creativity of young people who are on the move, we can’t use our established habits.”

Heath’s phrasing echoes the title of Audre Lorde’s essay on feminism and racism:  “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”. It suggests that current education efforts are self-defeating dead ends. Her metaphor is both telling, and dire:

“The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”. It suggests that current education efforts are self-defeating dead ends. Her metaphor is both telling, and dire:

We can’t look under the streetlight to find any keys we think we may have lost with regard to creativity. After all, schools are where the light has always been; that’s not where the light is now with respect to creativity.

That light has been extinguished by the narrowing curriculum and the obsessions with what can be measured and tested.

The next big gun brought to the the battle is Howard E. Gardner, a professor of cognition and education at Harvard University. In Five Minds for the Future he considers creativity one of five key ways of thinking—along with discipline, synthesis, respect, and ethics—that will be essential for young people to succeed in the future.

The Creating Mind – the capacity to uncover and clarify new problems, questions and phenomena – breaks new ground, puts forth new ideas, poses unfamiliar questions, conjures up fresh ways of thinking, arrives at unexpected answers.

And this is the scary part. When everything that can be has been automated and outsourced Gardner says:

Only individuals who can regularly go beyond the conventional wisdom will be valued.

If he is even close to right – and he is not alone in his thinking – then the pressure is on, the writing is on the wall and the urgency is now. And all the test taking ability in the world can only take you so far:

While cognitive capacities are obviously valuable for creating, only those of a robust, risk-taking personality and temperament are likely to pursue a creative path.

So what to do?

How do schools nurture, foster, grow. encourage, develop and incubate the essential survival skills of the creating mind defined as the the capacity to uncover and clarify new problems, questions and phenomena.

How do schools nurture, foster, grow. encourage, develop and incubate the essential survival skills of the creating mind defined as the the capacity to uncover and clarify new problems, questions and phenomena.

More arts in the curriculum? Is that the answer? Well – surely they can’t hurt but we need to be wary about the unfounded claims of the transfer of skills.

I’ve written about Ellen Winner before in How the Arts Deepen Student Thinking She’s is a professor of psychology at Boston College and with Lois Hetland associate professor of art education at the Massachusetts College of Art wrote

“Art for Art’s Sake” in The Boston Globe, September 2, 2007.

Both are also researchers at Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

It is well established that intelligence and thinking ability are far more complex than what we choose to measure on standardized tests…. They reveal little about a student’s intellectual depth or desire to learn, and are poor predictors of eventual success and satisfaction in life.

At the Learning and the Brain conference Winner said that in a continuing series of studies on arts education and creativity, she had found “very little evidence that studying the arts improves grades or test scores, or that studying the arts improves creativity.”

At the Learning and the Brain conference Winner said that in a continuing series of studies on arts education and creativity, she had found “very little evidence that studying the arts improves grades or test scores, or that studying the arts improves creativity.”

These transfer claims have been posited without any particular mechanism; there’s a lot of magical thinking going on.

Risk-taking and the ability to take failure in stride appear be critical elements of creativity.

Shirley Brice Heath’s decades long ethnographic research is useful here. She and her colleagues have found positive risk-taking common among the most creative students:

Risk we tend to think of in negative terms, but high risk in play is so endorphin-loading and high-energy, so it’s part of what keeps kids engaged in creativity.

The ones that emerged as most creative, … they used their play as work. They were very difficult to disengage from play.

To a person, they disliked, avoided, subverted education if it was not related to what they saw as their interests. They never seemed to think about whether they were supposed to be learning or doing what it was that they were learning and doing.

Schools of course – even the very best of them – are not generally structured to support that kind of risk-taking. And they certainly don’t usually appreciate or value subversive thinking. They are, understandably, structured for more conventional routes of success that inadvertently often stifle students willingness to take risks. Here’s Robert J. Sternberg – intelligence and creativity expert – now provost and senior vice president of Oklahoma State University in Stillwater on the topic

Schools of course – even the very best of them – are not generally structured to support that kind of risk-taking. And they certainly don’t usually appreciate or value subversive thinking. They are, understandably, structured for more conventional routes of success that inadvertently often stifle students willingness to take risks. Here’s Robert J. Sternberg – intelligence and creativity expert – now provost and senior vice president of Oklahoma State University in Stillwater on the topic

Risk is essential to creativity, … but if you want to get into the good college and the good graduate school and the good job, you don’t want to take too big a risk. Schools often encourage you to do the opposite of what you’d need to be creative.

Teaching Play

Ms. Winner made the distinction between disruptive, “revolutionary” creativity—for example, a Pablo Picasso who develops a new style of painting—and more general creativity, such as someone painting in the Cubist style that Picasso helped pioneer.

It’s not at all clear to me that this [revolutionary] kind of creativity can be cultivated, though perhaps it can be asphyxiated.

Even without knowing the secret sauce and magic formula it is not impossible to imagine how schools can help students go beyond test prep, mastering content knowledge and teaching how to perform specific skills.

Even without knowing the secret sauce and magic formula it is not impossible to imagine how schools can help students go beyond test prep, mastering content knowledge and teaching how to perform specific skills.

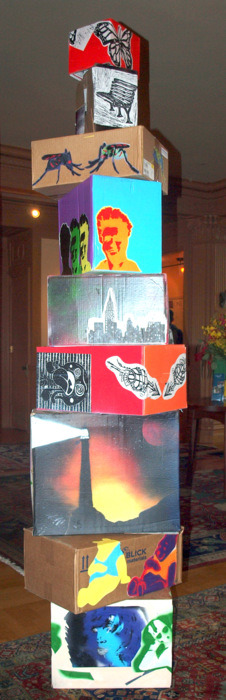

I see the school-based recipe as starting with teachers: space to imagine, room to create, time to play, colleagues to play with, encouragement to stretch and experiment, and permission to fail.

And the trouble often is: Too much, too much stuff, to do. And it gets in the way.

But the research is clear: We need to help kids learn to fail, seek alternatives, work through obstacles as ways to incubate the potential for creative problem solving.

And of course: There is no alternative to hard work and perseverance when it comes to the route to discovery and unique creativity. We have to teach that too. The obstacle along the way, the mistake, the failure the accident – it may be just what we need.

12 thoughts on ““Not where the light is”: Schools and Creativity”